During the 44th ASEAN Summit in Vientiane in October Thailand offered to host informal talks or track 1.5 dialogue among ASEAN member states in the coming December to find a solution to Myanmar conflict crisis, which was sparked by the military coup in February 2021 creating a civil war situation where thousand were killed and millions were displaced.

At the ASEAN Foreign Ministers Meeting, Thai FM Maris Sangiampongsa said his country is ready to host an extended informal consultation on the situation in Myanmar, following consultation with current ASEAN chair Laos.

Thai Foreign Ministry spokesman Nikorndej Balankur also announced the offer in an online press briefing on the first day of the ongoing ASEAN Summit and attendant meetings in Vientiane.

He said the proposal is backed by both Laos, the outgoing chair, and Malaysia, the incoming chair, and therefore likely to come to fruition, according to the Bangkok Post report.

However with the unstable political future of the ruling Pheu Thai party due to the controversy of facing dissolution by the Constitutional Court, the proposed ASEAN December informal meeting isn’t quite certain to materialize.

But first let us look at the past informal talks where Thailand had been involved.

Previous informal talks

Asian Forum for Human Rights and Development and Indonesia-based human rights organization, Komisi untuk Orang Hilang & Korban Tindak Kekerasan (KontraS), on June 21, 2023 released a joint statement, which lashed out at the Thai-led so-called ‘Track 1.5’ dialogue informal talks on Myanmar crisis on June 19, 2023.

Reportedly, “Track 1.5 is a series of informal meetings which began in March 2023. It intends to open additional channels of dialogue among stakeholders affected by the Myanmar crisis. It also seeks to foster mutual trust and confidence.”

The meeting was the third of its kind, which followed the ones held in Thailand and India in March and April 2023, respectively. This third meeting included a mix of government officials participating in an unofficial capacity as well as members of the academia.

“Notably, the meeting previously held in India was hosted and attended by representatives from China, Thailand, Laos, Bangladesh, Cambodia, and Indonesia. While the Myanmar military junta was able to attend the said meeting, the National Unity Government (NUG) – Myanmar’s elected civilian government – was not even invited,” according to the joint statement published by Forum-Asia.

Not surprisingly, Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) on June 22, 2023 publicized a report emphasizing the rejection from various concerned quarters as follows:

“Myanmar’s opposition National Unity Government, civil society representatives, and other ASEAN leaders denounced the meeting. Foreign Minister Retno Marsudi of Indonesia, the current chair of ASEAN, said in a letter declining the invitation that there was no ASEAN consensus to “re-engage or develop new approaches to the Myanmar issue.” Similarly, a press release from the Malaysian Ministry of Foreign Affairs said, “it is important that ASEAN demonstrates its unity in support of the ASEAN Chair and ASEAN processes.” Although Thai foreign minister Don Pramudwinai did not disclose details from the meeting, he pushed back against the criticism, saying Thailand has a vested interest in resolving the crisis in its neighbor and that other ASEAN countries “should be thanking [Thailand].””

“On June 19, Thailand’s caretaker government hosted an informal meeting in Pattaya on the civil war in neighboring Myanmar. Thailand, Laos, and the Myanmar junta were represented by their foreign ministers, while Brunei, Cambodia, the Philippines, and Vietnam, along with China and India, sent lower-level officials. Indonesia, Malaysia, and Singapore refused to attend,” according to CSIS.

No doubt the Forum-Asia’s part of the joint statement that followed also reflected ASEAN member countries like Indonesia and Malaysia: “Thailand’s attempt to re-engage with Myanmar’s military rulers through an invitation to participate in the Track 1.5 meeting could be interpreted as an endorsement and legitimization of the junta’s brutal actions. It also undermines the people’s long struggle for democracy, human rights, and justice. The one-sided initiative made by Thailand has also been publicly rejected by the Government of Indonesia – as the current Chair of ASEAN 2023 – and by the Government of Malaysia for not only threatening the unity of ASEAN but also for worsening the geopolitical tensions in the region.

In the same vein, the Singapore was also on the same page although no official rejections were made public.

Moreover, The Diplomat on June 21, 2023 reported: “(T)he meeting has been roundly criticized on a number of counts. The first is the inclusion of the military junta’s foreign minister, Than Swe, which effectively undercuts ASEAN’s established policy of not inviting political representatives from the military administration to high-level meetings of the bloc. The second is the way that the meeting could undermine efforts by current ASEAN chair Indonesia to broker inclusive talks between the military junta, the opposition National Unity Government (NUG), and other important players – one of the goals of the Five-Point Consensus.”

Thai decision-makers hooked to dealing with the Myanmar junta

Looking at the track record of two Thai governments, which are the previous government of Thailand under Prime Minister Prayuth Chan-o-cha and Srettha’s Pheu Thai Administration, we would see that both opted to deal only with the Myanmar military establishment or junta and refused to give space to the anti-junta groups like the NUG and ethnic armed organizations (EAOs).

“Thailand defended its move (June 19, 2023 ASEAN informal talks), emphasizing that direct talks with Myanmar were necessary to protect Thailand because its territorial proximity with Myanmar had been creating refugee and border problems, and affecting badly their bilateral trade,” according to Ministrate: Jurnal Birokrasi & Pemerintahan Daerah, research piece titled, “Thailand Seeking to Re-engage Myanmar Junta with Asean: National Interest or Political Ambition?”

“The research finds that the policy to re-engage Myanmar junta with ASEAN was influenced by the Prime Minister’s (Prayuth Chan-o-cha) political interest, along with the need for Thailand to protect its national interests. Omnidirectional hedging strategy, in its relations with the US, China, and regional power house such as India, helps as well to explain the move Thailand made with regards to Myanmar and ASEAN.”

Omnidirectional hedging as a concept can be defined as a foreign policy strategy which “helps small and medium powers to avoid being entrapped in an ensuing great power rivalry in which the more straightforward strategic alignment choices would render them pawns of that power contestation,” according to Olli Suorsa, study titled, “Maintaining a Small State’s Strategic Space: Omnidirectional Hedging,” International Studies Association Hong Kong, 2017.

According to Suorsa, Omnidirectional hedging has three dimensions: diplomatic diversification, economic diversification, and security diversification.

In the same vein, Asia Pacific Centre for the Responsibility to Protect School of Political Science and International Studies The University of Queensland St Lucia Brisbane QLD 4072 Australia published a report, titled, “Responses of Thailand to Myanmar Crisis since the 2021 Coup”, writes:

“(T)his report argues that, over the periods of two administrations in three years, Thailand’s responses to the crisis in Myanmar have remained reactive and continued to pursue a business-as-usual approach towards the military regime in Myanmar.”

“(T)he report concludes that Thailand could have done more by pursuing proactive engagement with Myanmar, but that may require comprehensive and concrete foreign policy action and the important role of active agents of change on the Thai side.”

Concerning the Thai policy on Myanmar, the same report outlined five key features or findings over the last three years since the February 2021 coup in its conclusion, which are:

- Perceiving the Myanmar Military as the Strongest Establishment. From the point of view of the Thai government and bureaucrats, engagement with the Myanmar military is seen as favorable because it has been able to consolidate political power for a long time. For this reason, Thailand has continued to maintain a business-as-usual approach towards the military-led SAC administration.

- Reactive Policy. Regardless of who is in power, Thailand has yet to develop a more concrete proactive policy and response to the situation in Myanmar. Currently, Thailand’s foreign policy actions and worldviews remain reactive.

- Preference for Bilateralism. In pursuit of its reactive responses towards Myanmar, it is also clear that the Thai government prefers a bilateral engagement with Myanmar. This is reflected in the way Bangkok has developed its own approach in parallel with the ASEAN initiatives.

- Lack of Inclusive Engagement with Other Stakeholders in Myanmar. Since the February 2021 coup, the Thai government’s engagements with Myanmar focused on the SAC with minimal to almost non-engagement with other stakeholders, including parallel political institutions emerging after the coup, such as the NUG and (National Unity Consultative Council) NUCC. This is also due to the perception of Thai officials that the Myanmar military remains the only viable institution in the country.

- Importance of Agents of Change. Changing the direction of Bangkok’s Myanmar policy or actions certainly requires agents of change who are keen on both pursuing initiatives and managing Thailand’s strategic interests.

Ruling Pheu Party facing dissolution

During nearly a year of Srettha Thavisin premiership from 22 August 2023 to 14 August 2024, two outstanding tasks regarding Myanmar conflict issue could be mentioned. One is the relatively proactive stance of Myanmar by Sihasak Phuangketkeow, a retired diplomat and former Permanent Secretary of the Foreign Ministry who served as a vice minister to Foreign Minister Panpree Bahiddha-nukara. On April 9, 2024, Srettha called for a meeting with key security policy personnel, including Foreign Minister and Vice Minister Sihasak, the Chief of Armed Forces, the Army Chief, and the Secretary General of the National Security Council and eventually formed the Ad Hoc Committee Administering Situations in Myanmar. The other is the formalization of humanitarian initiative and humanitarian assistance in order to engage with parties inside Myanmar in a constructive manner, which the Myanmar military junta also endorsed.

But “with the cabinet reshuffle on April 28, 2024, which subsequently led to the resignation of Foreign Minister Panpree, progress in the work of Thailand’s Myanmar Committee was stalled because his resignation also meant the termination of all political appointees under Panpree, including Sihasak,” according to the same report mentioned above.

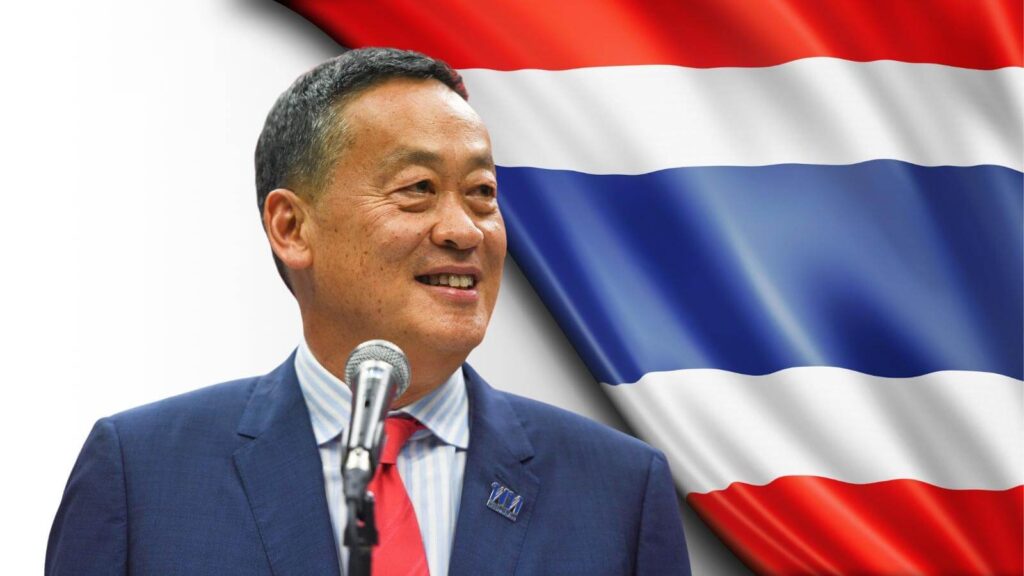

Four months later Srettha was removed by Thailand’s Constitutional Court for appointing a minister with a criminal conviction. Paetongtarn Shinawatra took over the premiership since August 16, 2024 but nothing has been known on how the policy on Myanmar will look like so far, even though her government is said to be pitching for more informal talks among ASEAN members and with the possibility of employing all-inclusive dialogue for all Myanmar stakeholders.

However, the planned ASEAN informal track 1.5 dialogue in December 2024 is set against a backdrop of political uncertainty in Thailand, particularly concerning the Pheu Thai ruling party. The party is currently facing a dissolution petition filed with the Election Commission, which may lead to further legal challenges if the case is forwarded to the Constitutional Court. This situation raises questions about the stability of the government and its ability to host international dialogues. In short, the upcoming Thai hosted informal ASEAN dialogue is uncertain although it could be pulled through depending on political developments leading up to that date.

Outlook

Regardless of the uncertainties to hold the planned informal track 1.5 dialogue, if ever it is going to materialize, the Thai decision-makers may have to ponder on its betting only on the Myanmar military establishment so far to become more proactive, which means to make the meeting all-inclusive, especially involving all the stakeholders within Myanmar. In other words, the participation of NUG, EAOs, political parties, civil society organizations and of course, the military junta.

For now, the junta and anti-junta political positions are polarized, with the junta’s surging confidence due the recent backing of China against its opponents and gearing to wrestle back the more than fifty percent of the captured territories from the anti-junta forces countrywide. It has been doing aerial bombing on anti-junta forces captured territories indiscriminately on civilian targets, although large scale infantry pushes have not occurred yet.

On the other hand, the anti-junta groups are also of the opinion that negotiation with the junta will be possible only if the military leaves the political arena for good and acceptance of the transitional justice.

Thus, Thailand has to fulfill a tall order to bridge the gap of warring parties and to do that it may have to be very proactive and can’t afford to dwell on the “Omnidirectional hedging strategy”.

In this sense, with the China openly opting for the junta which inevitably means going against the Myanmar people’s aspirations, not to mention the US and West backing of anti-junta’s democracy movement, Thailand may have to do something for its own benefit, first and foremost for its border security, spillover effect, and including acting as a reliable, neutral mediator and so on. The all-inclusive dialogue process for all stakeholders within Myanmar, rather than just betting on the junta as it usually does, may be an opener to wider venue of peace negotiation process to lessen the political-divide between contending parties and eventual resolution. Who knows?

Leave a Comments