On November 27, ICG published a report titled: “Fractured Heartland: Shan Politics and Conflict in Post-coup Myanmar,” which dwells on the assumption that China’s handiwork of siding with the Myanmar military junta and empowering the non-Shan ethnic armed organizations (EAOs) or ethnic resistance organizations (EROs) in an attempt to stabilize the situation, may have a profound negative effect, especially for the Shan/Tai majority.

The Shan called themselves “Tai”.

The report argued that side-lining the Shan majority from political decision-making power in Shan politics, intentionally or unintentionally, may deepen Shan grievances and inflaming anti-Chinese sentiment nationwide, as Beijing is being seen as shoring up the hated Myanmar’s tyrannical military junta by the whole country’s population, except of course for the small percentage of junta’s backers and its cronies.

The report’s concluding paragraph summed up the whole intended suggestion and assumption as below: “No settlement in Shan State will endure without political change in Myanmar as a whole. But by addressing immediate risks of escalation, fostering inclusive governance, and ensuring that Shan voices are part of today’s opposition political structures and any future national dialogue, national and international actors can help prevent a dangerous spiral. The alternative is a fractured Shan heartland where grievances deepen and inter-ethnic tensions sharpen, undermining the prospects for a more peaceful post-regime future for the state and the country.”

It is indeed peculiar and even shameful for the majority Shan that they are being looked down as pitiful people, unable to fend for themselves, despite having two strong Shan armies of more than 30,000 in combination, according to a conservative estimate.

However, the goodwill of ICG portraying and linking the Shan’s grievance, or rather the outrage, with the whole country’s liberation struggle from tyrannical military dictatorship system, which is a necessity cannot be overlooked and credit have to be given for highlighting the Shan majority frustration.

First, let us look at how this empowerment of the non-Shan EAOs, especially the Kokang or Myanmar National Democratic Alliance Army (MNDAA) and Ta’ang National Liberation Army (TNLA), with barely 300,000 and 500,000 population respectively, could control so much land where the majority of the Shan lives, together with a smaller percentage of other non-Shan ethnic groups.

According to the survey Shan population is estimated to be about 3 million only in Shan State, and within the whole union 5 million.

The rise of non-Shan EAOs after the military coup

Following the military coup in February 2021, nationwide resistance against the military junta went on for a few months until it was brutally cracked down. Within a few months, the people’s uprising transformed into armed resistance when they found out civil disobedience and rallies wouldn’t work to fulfil their democratic aspirations. However, in October 2023, the Three Brotherhood Alliance (3BHA) launched Operation 1027 after painstaking preparation for some years to launch the offensive, according to the Alliance.

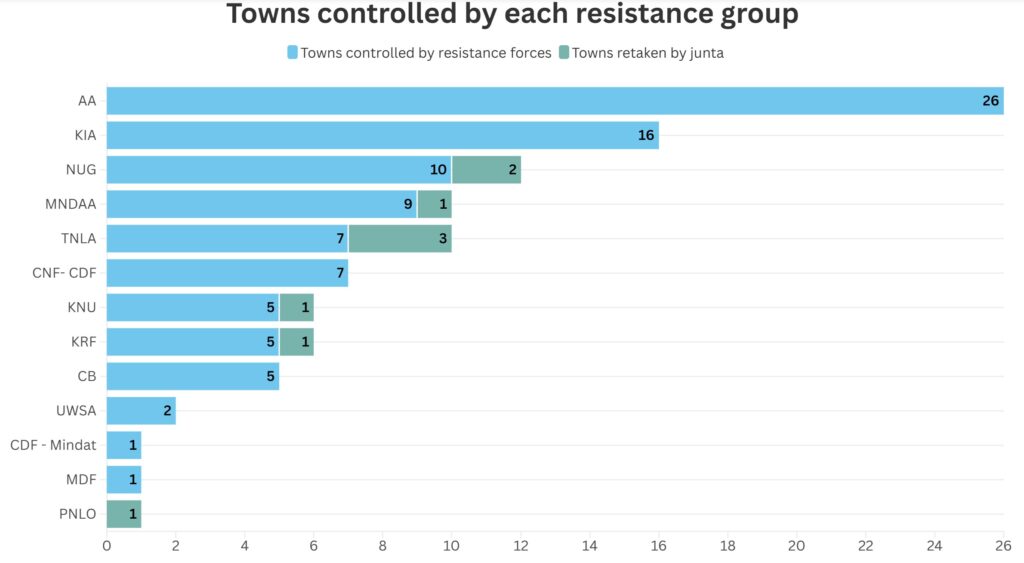

During the operation, the MNDAA seized 10 towns, including Chinshwehaw, Laukkaing, Konkyan, Mawhtike, Hpawnghseng, Monekoe, Kyugok, Kunlong, Tamoenye, and Lashio. The TNLA captured 12 towns – Manton, Moemaik, Monglon, Mongngaw, Nawnghkio, Kyaukme, Namhsan, Namtu, Namkhan, Kutkai, Moegok, and Hsipaw.

The Arakan Army (AA) launched its own offensive on 13 November, taking 21 towns across Rakhine and southern Chin State, including Paletwa, Kyauktaw, Mrauk-U, Minbya, Myebon, Ponnagyun, Buthidaung, Rathedaung, Ann, and Gwa.

These territorial gains have significantly influenced the military dynamics in the region, showcasing the coalition’s operational effectiveness against the military junta in Myanmar.

All these came about as the military junta was unable to prevent the EAOs from gaining ground, due to its overstretched forces, which could no longer stop their local allies or contain their adversaries.

Thus since late 2023, the 3BHA, particularly the TNLA and MNDAA took over the junta’s controlled areas, where the Shan majority resides, leaving non-Shan armies in control of a swathe of the state’s north, including areas historically held by Shan armed groups.

However, while the victories were credited to the 3BHA in general, it should be noted that it has been supported by a range of other armed groups during Operation 1027. These include the Bamar People’s Liberation Army (BPLA), the People’s Liberation Army (PLA), the Mandalay People’s Defence Force (Mandalay PDF), and the Mogoke Tactical Command (PDF), all of which are aligned with the National Unity Government (NUG) and have fought alongside the 3BHA. Additionally, the Karenni Nationalities Defence Force (KNDF), the Chin National Defence Force (CNDF), and other local resistance groups such as the Danu People’s Liberation Front (DPLF) and the Burma National Revolutionary Army (BNRA) have also participated in the operation.

The BPLA, PLA, Mandalay PDF, and Mogoke PDF are primarily composed of young fighters aged 20 to 30, known for high aggression and battle readiness.

The Kokang News Network on January 3, 2023, reported that the non-Kokangnese 611 Ethnic Nationalities’ (Taingyinthar) Brigade held a graduation ceremony at the military training ground attended by 1,229 soldiers, including officers, overseen by Yang Guanghua, deputy chief of staff of the MNDAA.

Prior to it Brigade 511, the batch one was formed, followed by formation of Brigade 611, Brigade 76 and Brigade 707 were subsequently, all non-Kokangnese outfits reportedly to fight and uproot the military junta and establish a federal democratic union.

However, the Operation 1027 second phase fizzled down as China changed stance and pressured the MNDAA and TNLA to back down and even demanded them to give back some towns captured back to the military junta. This is despite the fact that China has given a green light to launch Operation 1027 in order to dethrone or wipe out the Kokang Self-Administered Zone’s ruler, which was placed there by the military junta and was the main culprit of illegal online cyberscam operations that China wanted to get rid of. Reportedly, it scammed China’s institutions and civilians in billions of Yuan and even killed its intelligence operatives, which China couldn’t forgive or overlook.

To date, key towns recaptured by the Junta from 2024 to 2025 are Hsipaw, Kyaukme, Nawnghkio, in Shan State; Thabeikkyin in Manadlay Region; Kawlin in Sagaing Region; Demoso and Mobye in Karenni or Kayah State.

Lashio, known as the northern capital of Shan State was given back to the military junta after the MNDAA was pressured by China, reportedly through detention of its leader Peng Deren, who serves as the Commander-in-Chief and Chairperson, including sanctions and freezing of the MNDAA and its leadership assets in China.

As of December 2025, the TNLA have agreed to withdraw from key towns including Mongmit or Momeik and Mongkut (Mogok), effectively sending back or disbanding joint operations with allied voluntary forces such as the People’s Defence Force (PDF), Mandalay PDF, and Danu People’s Liberation Army (DPLA). This move followed ceasefire talks in Kunming, China, in late October 2025.

Accordingly, Mogok a ruby-mining hub in the Mandalay Region and Mongmit or Momeik, in northern Shan State were returned to Myanmar military control in late November/early December 2025 as a result of a China-brokered ceasefire agreement with the TNLA.

The current situation could be said as nuanced. The TNLA, which had seized both towns in 2024, agreed to withdraw its troops and hand the areas back to the junta under intense pressure from China. As of early December 2025, junta troops have entered the towns and established positions at key locations, including entry/exit points, schools, and hospitals.

However, despite the TNLA’s withdrawal from the main towns, other resistance forces like the People’s Defence Force (PDF) and the Kachin Independence Army (KIA) remain active in the surrounding townships and are committed to fighting the junta. Skirmishes and clashes were reported immediately following the junta’s re-entry into Mogok.

In essence, while the administrative centers of Mogok and Mongmit are back under nominal junta control due to the ceasefire, the wider townships remain contested, and the situation is fluid and tense.

Thus, it can safely be concluded that the success of TNLA and MNDAA in capturing towns were partly due to the manpower reinforcement from Burmese heartland, Anyar, also partly from Karenni State and the Southern Shan State.

Inaction of two Shan armies

ICG report outlined three core factors: “Since Myanmar’s 2021 coup, non-Shan armed groups have taken control of Shan-majority areas in Shan State, side-lining Shan armies and politicians; Shan State is Myanmar’s largest and most strategically important state, central to trade with China and illicit economies. Escalation in its web of armed conflicts would be destabilizing; (and) The Shan need greater security and better political representation. Non-Shan groups should include Shan people in local government and work to protect Shan civilians in areas they control.”

But the most important thrust in portraying the Shan/Tai majority population’s frustrated mindset is the following remark made by ICG report. The report writes: “Shan, especially the youth, lament stagnant leadership that fails to stand up to the regime or defend their areas from encroachment by non-Shan forces.”

Undoubtedly, the added details that follows actually reflect the mood and feelings of the majority Shan/Tai population: “For Shan people, the new order is profoundly disempowering. Shan, especially the youth, lament stagnant leadership that fails to stand up to the regime or defend their areas from encroachment by non-Shan forces. The two main Shan armed groups – the Restoration Council of Shan State (RCSS) and the Shan State Progress Party (SSPP), both of which have existed for decades – have refrained from fighting the regime and sparred occasionally with each other for control of territory and resources. Their credibility in the eyes of many Shan women and men has thus eroded. Meanwhile, on the political front, the leading Shan party, the Shan Nationalities League for Democracy (SNLD), which the junta has deregistered for boycotting its planned election, is not included in key opposition structures at the national level, such as the National Unity Government.”

The concern of the ICG report on the frustration of the majority Shan population is correctly described in the following paragraph.

“Grievances among the Shan are acute. Residents of areas now under TNLA and MNDAA control describe arbitrary taxation, forced recruitment, abusive administration and cultural exclusion. With Shan armed groups also accused of exploitative taxation and profiteering from drugs and scams, many Shan feel caught between predatory outsiders and unaccountable leaders of their own. Women are often particularly marginalised. The danger is that frustration hardens into a more defensive, exclusionary nationalism, undermining the ethos of peaceful coexistence with the state’s other ethnic groups that Shan leaders have long advanced and raising the risk of more inter-ethnic conflict.”

If one should describe the feelings of Shan majority in a few words, it will be “frustration and inferiority complex laced with the inability to meet the challenge of preserving their national identity, cultural heritage and sovereignty”.

Now let us see why the two Shan armies and lone political party, SNLD, that actually represents the Shan and all Shan State citizens are unable to do much for their people or electorate.

Probable reasons for inaction

The majority of the people countrywide are at lost why the two Shan armies, RCSS and SSPP sit out the nationwide people’s uprising and refuse to fight the military junta, needless to say of the Shan majority frustration, where they felt humiliated and looked down upon by the non-Shan EAOs, which now become their de facto ruler, instead of the Shan armies. Worse still is that they were unable to even protect them from non-Shan EAOs riding rough shod on them, belittle them and even destroyed their cultural and historical heritage, which are unbearable.

Ultimately key reasons and speculations include: Bitter Rivalry and Territorial Disputes; Diverging Political Alliances; “Bamar Power Struggle” Perception; External Influence (China); Economic Interests; Loss of Credibility & Stagnant Leadership; among others.

Bitter Rivalry and Territorial Disputes: The most significant factor is the long-standing, intense conflict between the RCSS and SSPP themselves. They are bitter rivals with overlapping territorial claims, and the fight for control of resources and territory in Shan State has often overshadowed the broader revolution against the junta. In fact, the SSPP and its allies (TNLA, UWSA) previously forced the RCSS out of much of Northern Shan State in intense fighting around 2021, and this internal conflict has continued despite attempts at a truce.

Diverging Political Alliances: The RCSS signed the Nationwide Ceasefire Agreement (NCA) with the previous government in 2015, which positioned it as part of the official peace process. After the coup, the RCSS has engaged in opaque negotiations with the junta, which has damaged its credibility with other resistance groups and some Shan people. It appears more inclined to cut a deal with the military than to fight alongside the broader anti-junta movement.

The SSPP is part of the Federal Political Negotiation and Consultative Committee (FPNCC), an alliance of powerful, non-NCA signatory groups led by the United Wa State Army (UWSA). The UWSA and other FPNCC members (until the Operation 1027 offensive) generally preferred a “winning without fighting” strategy, focusing on economic development and autonomy within their regions rather than head-on confrontation with the military. The SSPP has largely aligned with this position. It also has signed a State-level ceasefire with the military junta years ago, although not the NCA.

Ideological Difference and Personal Rivalry: Different ideological orientation, such as SSPP is left-leaning and for people’s democracy, while RCSS is for national democracy. Besides, RCSS playing proxy or proxy-like stance in relation to Thailand, while SSPP which is near to UWSA maybe taken as a semi-proxy to China, if not a fully fledged proxy like the UWSA. It should be noted that SSPP financial links and its war chess are believed to be stored in China, probably under UWSA cover, making SSPP dependent on it and playing UWSA’s second fiddle, besides also maintaining a sort of buffer zone for the UWSA territories, according to one senior SSPP functionaries, now retired, to this writer. Leadership rivalry, according to insiders was also intense between RCSS leader Sao Yawd Serk and SSPP leader Sao Parng Fah. Most importantly though is the mindset of both Shan armies’ leadership, that the Myanmar military junta cannot be beaten and thus only through dialogue or concession can they advance their political goal, which is either absurd or loss of their professed revolutionary goals.

“Bamar Power Struggle” Perception: Some leaders within both groups view the post-coup “Spring Revolution” as primarily a power struggle between the Bamar majority’s National League for Democracy (NLD) and the military junta, now known as State Security and Peace Commission (SSPC). They are hesitant to commit their forces to a conflict they see as a Bamar affair, preferring instead to pursue a federal system for Shan State independently. The perception however isn’t catering to the reality on the ground. Because for the first time in Burma’s modern history, the 60 percent or so majority country’s Bamar population are for the uprooting of military dictatorship system from political arena and for the genuine establishment of a federal democratic union. The countrywide armed rebellion is the testimony of such a changed mindset, which was hoodwinked by the Burmese military class for decades.

External Influence (China): China has significant economic interests and a desire for stability along its border in Shan State. The UWSA is heavily influenced by Beijing, and the SSPP’s close relationship with the UWSA means it also toes a line that avoids actions China might see as destabilizing, such as a full-scale war against the junta. China has historically pushed for ceasefires and stability, as seen with the recent return of Mogok and Mongmit or Momeik to junta control.

Economic Interests: Both groups operate in areas rich in natural resources and illicit economies (e.g., drug trade, illicit mining). The relative stability provided by ceasefires has allowed them to focus on these activities, which would be disrupted by full-scale warfare.

Loss of Credibility & Stagnant Leadership: This stance has led to significant criticism and an erosion of credibility among many Shan youth and civilians who wish to see their armies actively defend them against the junta’s regime and join the national revolutionary movement.

In summary, the Shan armies’ refusal to fully engage in the fight against the junta is not a sign of support for the military, but rather a reflection of deep-seated internal divisions and pragmatic decisions based on their own political goals, alliances, and survival strategies within the complex landscape of Myanmar’s conflict.

Ventil for the Shan frustration

The excellent description of the Shan psychological effects by the recent ICG report writes: “At present, however, rising nationalist sentiment among the Shan people has no effective outlet. The RCSS and SSPP are not playing an active role in the wider anti-regime struggle; nor, as noted, are they defending the Shan from the encroachment of other armed groups – offering no real resistance when these groups seized historically Shan areas over the last two years. On the political front, the SNLD is still active, but it is constrained, engaging little with revolutionary politics and staying out of what are widely expected to be Potemkin elections. Leaders’ wariness of open rebellion against the regime is shaped in part by memories of the military’s counter-insurgency campaigns of the 1970s and 1990s in Shan State, which inflicted enormous suffering on civilians.”

With the two Shan armies not undertaking meaningful actions to protect the Shan population and its literature and cultural heritage, the Shan youth found their outlets by joining other anti-junta outfits, as they were eager to fight the Myanmar military junta, which they consider to be the main enemy. Apart from that some frustrated Shans tried to organize themselves and find ways to vent their frustration.

“Against this backdrop, Shan people are already mobilizing in several ways. Some have voluntarily joined other non-Shan armed groups, including the TNLA, MNDAA and KIA, as well as various post-coup resistance groups including the Mandalay People’s Defence Force and the Karenni Nationalities Defence Force, to play a role in the post-coup revolutionary struggle or, in some cases, to help protect their home communities,” writes the ICG report that correctly mirrors the Shan youth reaction to the prevailing situation.

Another example is the reflection that the Shan population is willing to do everything in their own capacity in the face of two Shan armies indifference and for whatever reason refusing to come to their aids in preserving their national identity, sovereignty and national pride. This is none other than mobilization to form militias to take things in their own hand.

“An example is a group known as Sengli Möng Mao, formed in Namhkam in late 2023 by a prominent Shan monk soon after the TNLA seized control of the town,” writes the ICG report.

The RCSS was pushed out by the SSPP and TNLA combined forces, aided by UWSA since 2021, which the RCSS accused of the directive coming from China, as it is considered pro-West for having close relationship with Thailand. Reportedly, China didn’t want to see RCSS at its doorstep. SSPP is reluctant to intervene, probably because of its policy of maintaining good relationship with the allies. Or for whatever reason it may has in store. Thus the two Shan armies are not doing anything worthwhile for the Shan nation in the eyes of the Shan youth and patriots alike.

The monk was able to recruit some 2,000 from mostly Namhkam residents, who were given basic military training by the SSPP, but no arms. Alarmed the KIA and TNLA attempted to woo the group with promises of arming them. But they refused and stood by its defining mission to defend the Shan from groups representing other ethnicities, according to the ICG report.

Shan insiders from various sources with extensive knowledge told this writer that the Monk has been educated in Sri Lanka and probably received a degree in Buddhist studies like many other numerous Shan monks. He is said to be a Shan patriot, an able organizer and gifted orator. However, he eventually placed his group under the SSPP command because of the KIA and TNLA intense scrutiny.

It’s clear that rallying the Shans by tapping into their strong sense of nationalism and patriotism can quickly inspire them to take bold actions, especially when the message resonates deeply. One can only imagine how much stronger their support would be for an organization or army committed to fighting the Myanmar military junta, which they’ve despised for decades as an occupying and oppressive force, and openly defending the Shan people and their homeland from any invaders.

CSSU Manifesto

Generally speaking, the CSSU Manifesto reflects the vision of Shan leadership for a multi-ethnic Shan State where all groups live together harmoniously, reminiscent of the Shan State government formed in 1947 under Palaung Saohpa Khun Pan Sing, before the signing of the Panglong Agreement on 12 February 1947.

Established in 2012, the CSSU originally brought together two Shan armies (SSPP and RCSS), two Shan political parties (SNLD and SNDP), and various civilian organizations.

Its goals include political representation for the Shan people in national governance; preserving Shan culture, language, and traditions to foster identity and heritage; promoting economic development to improve living standards and opportunities in Shan State; and advocating for peace by resolving conflicts through dialogue and negotiation rather than armed confrontation.

The manifesto also serves as a platform to champion the rights and aspirations of all Shan State citizens, aiming for a peaceful, inclusive future for every ethnic group in Myanmar.

Analysis

The ICG believes that side-lining Shan armed groups and political parties, while empowering or allowing non-Shan armed groups to expand into Shan-majority towns, has had a negative impact, with China playing a key role as power broker.

While this has arguably led to some ceasefires and the possibility of reopening trade routes, these gains have only been partial.

According to the ICG, Beijing’s support for the regime has stoked public anger, and its preference for working with non-Shan groups risks deepening Shan alienation. The Shan resent outsiders dominating their areas and feel let down by leaders who failed to protect them.

The idea that China should help Shan State economically by promoting legal businesses, eliminating illicit ones, and persuading non-Shan groups to respect and involve the Shan in governance, granting them equality in all livelihoods, may be hard to achieve.

The Shan are a proud people unwilling to accept leniency from minority armed groups like the TNLA and MNDAA.

They believe they must take matters into their own hands regarding their identity and sovereignty, even though their two Shan armies remain hesitant to act boldly for their people and homeland.

The ongoing territorial expansion by TNLA and MNDAA into Shan areas—seen as neocolonialism—along with the suppression of Shan literature and cultural heritage, won’t be easily resolved, especially given the narrow ethnonationalism and expansionist ambitions of non-Shan armed groups. As noted, it’s a ticking time bomb at the core.

Leave a Comments