Every time a letter arrives from a ward or village administrator, mothers across Shan State feel the same fear: “Is my son on the list?”

That dread has become constant, weighing on families as they face an impossible choice—surrender their children to armed forces, pay large sums of money, or risk losing them forever.

Nearly two years after Myanmar’s military regime reactivated the People’s Military Service Law on February 10, 2024, forced conscription has intensified nationwide. The law, originally enacted in 2010 under former military ruler Than Shwe but never enforced under civilian governments, is now being implemented under coup leader Min Aung Hlaing to replenish military manpower following heavy battlefield losses.

Under the law, men aged 18 to 35 and women aged 18 to 27 are required to serve. As of December 16, 2025, the regime had opened 20 military training batches, recruiting an estimated 100,000 new soldiers.

On the ground, however, residents say recruitment increasingly resembles forced arrests, extortion, and human trafficking.

As young people flee towns and villages or go into hiding, local authorities say they can no longer meet recruitment quotas. In response, township administrators, immigration officials, and ward leaders have reportedly begun working with brokers to purchase substitute recruits—often from Central Myanmar—at prices ranging from 5 to 6 million kyats per person. Residents say officials then inflate the cost to 10–11 million kyats to extract personal profit.

“Now that administrators can’t find people anymore, the Immigration Director, Township Administrator, and Deputy Administrators have to find them personally. It has become like a trade in humans,” said Ko Sai (pseudonym), a resident of Namsang Township.

Since mid-January, authorities in Namsang, Kunhing, and Karli townships have issued notices ordering households to contribute 50,000 kyats to fund substitute recruits for the military’s 21st training batch. According to locals, payments vary by income level—wealthier families are asked to pay more, while even the poorest households, including those surviving by selling firewood, are forced to contribute.

“They collect even from families who survive by selling firewood. They say they can’t refuse orders from above,” Ko Sai said.

In Mong Tong Township, residents report being charged again despite having already paid three months of military service fees.

“It feels like a permanent tax. We’re struggling just to survive. I don’t know who to ask for help anymore,” said Sai Tip (pseudonym).

Double Burden: Junta and PNO Payments

In Pang Laung (Pinlaung) and Hopong townships, residents say they must pay both junta military service fees and financial demands imposed by the Pa-O National Organization/Army (PNO/PNA). Monthly household payments reportedly include around 10,000 kyats for junta service fees and 30,000 to 50,000 kyats for PNO/PNA military expenses. Vehicle owners are also charged a so-called “wheel tax” ranging from 50,000 to 200,000 kyats, depending on the condition of the vehicle.

“We pay the service fee, PNO military expenses, and taxes. Even if we don’t have money, we sell what we have. People are exhausted,” said U Kyaw Hein (pseudonym).

Residents say young people are being pressured not only to serve the junta but also to join ethnic armed groups, some of which claim enlistment will exempt recruits from junta conscription. In reality, locals report that families often end up paying multiple armed groups while still facing recruitment threats.

Recruitment Expands Across Northern Shan

In Lashio, where the military regained control of 12 urban wards after the Myanmar National Democratic Alliance Army (MNDAA) withdrew in April 2025 under Chinese pressure, the regime resumed household census checks on January 21, fueling fears of imminent recruitment.

“They took the names of my two sons and one daughter before. Now that ward elders are going door to door again, we are very worried,” said a Lashio resident.

At the same time, the MNDAA is reportedly enforcing recruitment in villages under its control outside Lashio. In the Nam Pawng area, village heads have been ordered to provide five recruits per ward, totaling 40 people. In areas such as Man Pyin, Man Sei, and Nar Nann, village elders have reportedly traveled to MNDAA bases to request exemptions due to a lack of eligible men.

“They say it’s just village militia duty, but they give uniforms, guns, and training—so we know they will make us fight,” said a Nam Pawng resident.

Meanwhile, the Kokang News Network reported on January 25, 2026, that the MNDAA released 500 detained junta personnel, even as civilians continue to be forcibly recruited.

When There Is No Way Out

The pressure has already turned deadly.

In Mong Ket village tract, Lashio Township, the United Wa State Army (UWSA) summoned village leaders in January 2026 and demanded 100 young men for military training. Days later, on January 20, a 40-year-old man named Sai Lot died by suicide after learning his name was on the recruitment list.

“Sai Lot was the main provider for his family. When he found out he had been selected, he saw no way out,” a resident told SHAN.

Residents say earlier UWSA militia training in 2025 left participants physically and mentally exhausted, with many fleeing immediately afterward due to harsh conditions and language barriers.

Youth as Hostages of Armed Power

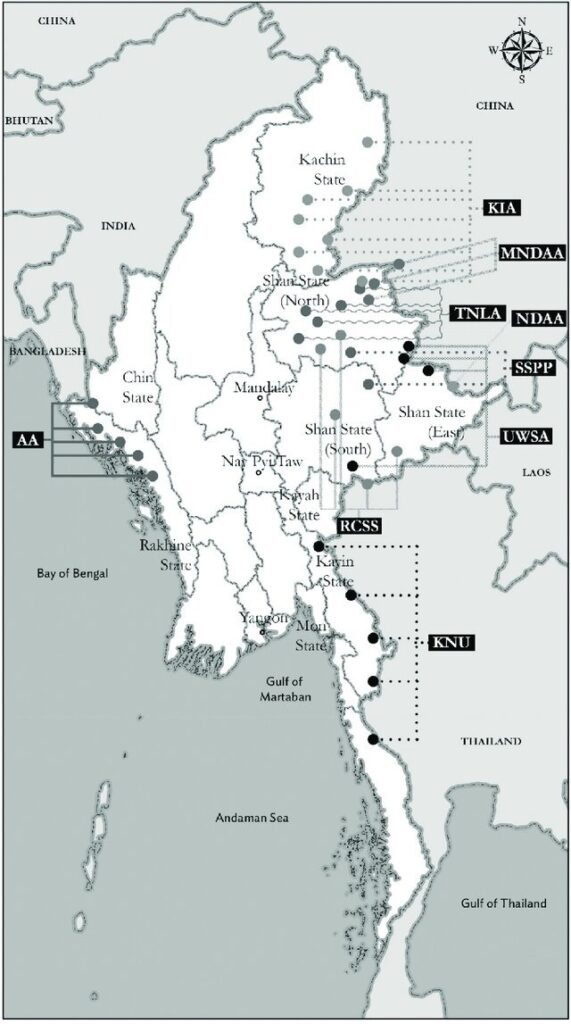

Across Shan State, residents describe young people as hostages of overlapping armed authority—caught between the military regime and ethnic armed groups, including the MNDAA, UWSA, PNO/PNA, SSPP, and RCSS.

Those who flee junta conscription often encounter similar pressure in ethnic-controlled areas. Families with financial means attempt to send their children abroad, while poorer households remain trapped between forced recruitment, extortion, or arrest.

“Nowhere is safe,” said a youth from Lashio. “We are afraid of the army, and we are afraid of armed groups. Young people don’t want to fight for anyone—we’re just being turned into hostages.”

For many families in Shan State, a military summons no longer feels like a legal obligation. It feels like a warning of loss—pushing parents and youth toward desperation, displacement, or, in the most tragic cases, death.

Leave a Comments