Most people believed the Myanmar election was entirely orchestrated by General Min Aung Hlaing as a way for him and his allies to secure an escape route. However, according to Deng Xijun, Special Envoy for Asian Affairs at China’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs, that’s not exactly the case.

Reportedly, according to the military junta’s media outlet The Mirror on December 29, 2025, Special Envoy Deng Xijun said: “I’m truly grateful and honored to have been invited by the Myanmar Election Commission to observe the process, especially the implementation of the election agreement between President Xi Jinping and Myanmar’s Interim President General Min Aung Hlaing, as well as the ongoing cooperation and coordination between China and Myanmar.”

On the same day, Foreign Ministry Spokesperson Lin Jian during the Regular Press Conference said: “The government of Myanmar held the first phase of the general election on December 28. Chinese observer mission and representatives from relevant countries and international organizations observed the voting on site. The voting process was generally stable and orderly, giving the election a smooth start. China hopes that the upcoming second and third phases of voting will also be smooth and enable the situation in Myanmar to stabilize and deescalate, help restore political normalcy, bring about more broad-based and stable peaceful reconciliation, and bring back stability and development at an early date.”

Two main issues are in play here. First, Xi Jinping wants Min Aung Hlaing’s military junta to gain more legitimacy by going through a general election process, allowing China to engage with it on a government-to-government basis, regardless of how fraudulent or unacceptable it may seem to the international community. For China, the important thing is that the process appears proper, as it cannot continue working with the coup regime to carry out and implement its many CMEC and BRI projects. Second, there’s the goal of establishing a stable military regime with a civilian front, resembling a one-party system, that can protect China’s political and economic interests over the long term—in other words, a Myanmar government aligned with Beijing’s preferences.

China’s pressure on junta and its future governance projection

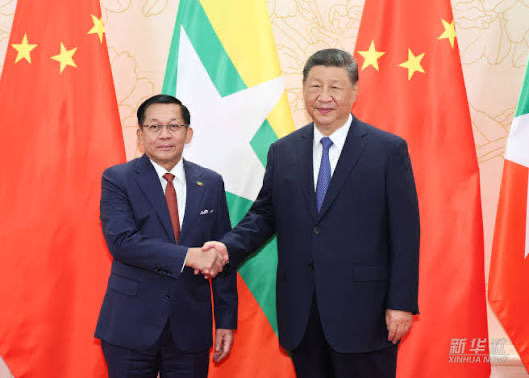

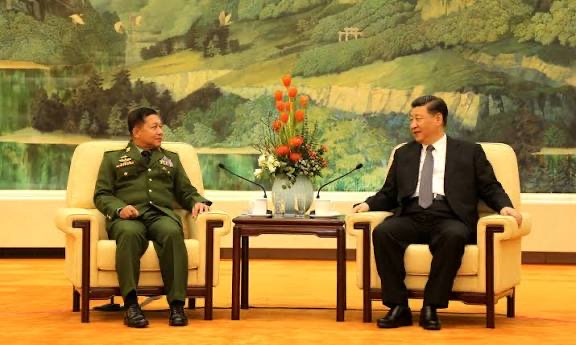

According to a recent BBC Report, a personal meeting with Chinese President Xi Jinping was a dream come true for the military leader, according to those close to him.

After more than four years after the coup, the Chinese president invited the Burmese military leader Min Aung Hlaing to Beijing. But the first step was he has to promise to hold elections, (which he probably did).

Seven memorandums of understanding (MoUs) were signed between China and Myanmar during the visit of military leader Senior General Min Aung Hlaing to China from August 30 to September 6, 2025.

China has said the military commission election, which came five years after the coup, was a result of an agreement between Min Aung Hlaing and Chinese President Xi Jinping.

Beijing, which has been calling the election an internal affair of Myanmar, (now) appears to have admitted that the military election was a result of China’s agreement.

“China wants a Myanmar government that is compatible with the military, not leaning towards the West, and is sticking to the 51 percent formula rule for Myanmar,” an adviser to the military commission told the BBC.

Myanmar’s holding of elections is an agreement between President Xi Jinping and military leader Senior General Min Aung Hlaing, China’s Special Envoy for Asia, Deng Xijun, told a briefing held by international election observers in Naypyitaw.

Although China supports multi-party democracy in Myanmar, it wants to create a single-party style administrative system, the military commission adviser said.

The Myanmar model China wants is for the government to have 25 percent military representatives (which actually is allotted by appointment according to the 2008 Constitution) and 26 percent civilian representatives who will support the military in the parliament.

“The idea is that Myanmar can have multi-party democracy. But to make decisions firm and stable, China wants one party to dominate. That’s the same as China’s one-party system,” he said.

“The military generals will control power. The elected civilian members of the parliament will be responsible for approving the budget and laws. They will scrutinize the contracts and projects.” He explained China’s preference for the parliament and the government.

“The desire to establish a committed, solid, strong central government in Myanmar is very earnest on the part of the Chinese,” the military commission adviser said, citing what he knew.

Recent anti-China tendency

China has made no effort to hide that the military junta has become its puppet, now seen as a self-governing state that has abandoned necessary ethics, openly declaring this both at home and abroad. This has earned Min Aung Hlaing the label of China’s puppet president and dealt a heavy blow to China-Myanmar relations.

China has even stated that the recent election was agreed upon by President Xi Jinping and Min Aung Hlaing, a claim made by Chinese Special Envoy Deng Xijun. Min Aung Hlaing can no longer deny his role as China’s puppet.

The notion that “China is on our side” serves as propaganda to rally domestic supporters and subordinates, with hopes that a post-election government will gain China’s immediate recognition, paving the way for acceptance from other neighbors and Russia.

Such recognition could also lead to special economic deals, like the Kyaukphyu deep-sea port, railways, Myitsone, and mineral projects, whenever China desires.

While China once claimed neutrality in Myanmar’s affairs, its open backing of the election shows its focus is now squarely on protecting its own interests. This might give the military regime a short-term boost, but it defies the will of the Burmese people and risks deepening the conflict.

Public opposition and anti-China sentiment are likely to grow, making it harder for the junta to govern. Making such remarks after the election also is tantamount to being dishonest to the people. Those who opposed the election will become even more distrustful of China, seeing clearly that their democratic aspirations are being ignored in favor of supporting an election that prolongs the military coup. People in Myanmar may start questioning why they should tolerate Chinese domestic investments when China has openly sided with their adversaries, the military junta.

ASEAN could face division, with its five common positions potentially weakened.

Aware of this, Malaysian Prime Minister Anwar Ibrahim cautioned early on that ASEAN would “assess the situation in Myanmar after the first round of elections and avoid any premature legitimization of any organization.” China has openly influenced Myanmar for its own long-term interests rather than stability, and the Myanmar issue “risks becoming a buffer zone for a new Cold War.” Anwar’s comments have slowed the plans of China and the military council, making it harder for the regime to gain diplomatic legitimacy while boosting the revolutionary forces’ presence on the global stage. Whether the United States will offer support beyond non-military aid remains uncertain, and the people’s revolution now faces a more complex international political landscape than ever, according to Hla Soe Wai in his recent FB posting.

Likewise, the international community’s response, including that of the United States, to China’s apparent move to treat Myanmar as its proxy state could mark a major turning point for the country. A typical U.S. administration might invoke the BURMA Act to push back against China’s influence. Meanwhile, Western nations like the EU, UK, and Canada are likely to increasingly label the election as “illegal” and a “sham,” deepening divisions within the global community, he reasoned.

Similarly, TM Media recently criticized the junta’s first-phase election results from December 28, 2025.

Journalist Ko Thein Myat highlighted the low voter turnout—20 to 30 percent according to locals, and about 50 percent by the junta’s supporters.

Reports claimed the junta used intimidation tactics such as denying travel permits, enforcing conscription, and restricting the registration of overnight guests. These threats were allegedly carried out by officials at all levels, from department heads to subordinates, in both civilian and military institutions.

Widespread vote rigging was also alleged, especially in advance voting, with complaints even from pro-junta parties who received little to no votes, as most went to the junta’s USDP. Calling it a case of “political heartbreak,” Ko Thein Myat said parties like those led by Ko Ko Gyi, U Aye Maung, and Sai Aik Pao ended up empty-handed.

In the end, he predicted, junta officials will simply trade uniforms for civilian clothes to take government seats, making the regime even more militarized than previous ones.

Analysis

Considering the circumstances, the two objectives of Xi Jinping, which are holding Myanmar’s elections and making the junta’s in civilian clothes more acceptable in international arena, should be considered party fulfilled if not yet hundred percentage.

The three-phase election is going to be concluded as scheduled by the end of January 2026, even though the acceptability by the international community will be still largely vague, undecided to majority rejection.

The aftermath of the elections of which lending legitimacy will become essential will be the bone of contention between the junta and the anti-junta opposition. To date, the UN hasn’t recognize either the junta or the NUG and its allies, although China, Russia, Belarus, Iran, North Korea are definitely on the side of the junta.

The outlook as a whole for Myanmar remains grim, with the civil war likely to escalate as factions continue resisting military control, potentially dragging the country into prolonged unrest. The military junta may respond with harsher military action in defiant regions.

The junta’s bid to frame elections as progress toward democracy could backfire, deepening its legitimacy crisis and sparking more civil disobedience or armed push-back.

On the global stage, widespread condemnation may bring tougher sanctions and reduced foreign aid, worsening the humanitarian crisis, while China’s role as a stabilizing force could shift alliances and shape Southeast Asia’s political dynamics.

Genuine democratic dialogue seems out of reach, with no credible opposition or meaningful military engagement, making the road back to democracy especially challenging.

Rising ethnic nationalism, fueled by resistance to junta control, could further complicate future reconciliation. While the post-election future is uncertain, the consequences will likely ripple far beyond Myanmar, impacting both regional stability and international relations.

Leave a Comments