From the sandbagged banks of the Sai River, the scene across to Myanmar is one of quiet devastation. Red tin roofs and crumbling storefronts in Tachileik stand as remnants of a town battered by recurring disasters.

“If there’s another flood, we don’t know where we’ll end up,” said Nang Hom (pseudonym), a resident of eastern Shan State, her voice trembling with uncertainty.

Though Cyclone Yagi made landfall in Vietnam in early September 2024, its reach extended far inland, triggering unprecedented floods in Tachileik, a town perched over 1,200 feet above sea level. In mere hours, rain-swollen rivers surged beyond their banks.

“Two hours of rain was all it took. The river rose without warning and turned into a torrent. Mud and silt surged into our homes and shops, covering everything in red sludge,” Nang Hom recalled. Cleanup efforts had barely begun when another flood followed. “Last year we had three floods. This time, the damage is beyond anything we’ve seen.”

A Tale of Two Towns

Mae Sai and Tachileik lie across the river from each other, but their flood responses couldn’t be more different.

On the Thai side, the Royal Thai Air Force mobilized swiftly: airdropping food and water, evacuating residents, and coordinating relief. Meanwhile, in Tachileik, residents say they were largely left to cope alone.

“People help each other, but there’s no plan. Homes were wiped out overnight,” said Ko Kyaw (pseudonym). “Authorities only clear a few main streets. The rest is up to us.”

In Talaw Ward, one of the worst-hit areas, schools, homes, and shops remain caked in mud. Local efforts focus on renting trucks to haul away debris, with little support from the township administration.

Still, some signs of cooperation have emerged. On October 9, 2024, Thai and Myanmar officials met to discuss long-term flood prevention. Thailand proposed keeping the Mae Sai River at a minimum width of 30 feet and has already built a 5-meter-high embankment on its side, with plans to construct a road along it. Residents on the Thai bank have been promised compensation and relocation, but implementation remains pending.

Flooding Across Shan State

Tachileik wasn’t alone. Townships including Kengtung, Mong Yawng, Mong Hsat, Mong Nai, Mawkmai, Langkho, and Nyaung Shwe were also inundated. In Langkho Township alone, about 1,000 homes and 3,000 acres of farmland were submerged.

According to the UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (UNOCHA), nearly one million people across Myanmar were affected by the September floods, with hundreds killed.

Deforestation, Mining, and Environmental Collapse

Experts trace the root of these worsening disasters to deforestation and unchecked resource extraction.

“When forests vanish, water sources collapse too. Everything is connected, forests, land, biodiversity, and water,” said environmentalist U Win Myo Thu. “Cyclone Yagi showed how fragile Myanmar has become.”

Shan State, rich in forests and minerals, has suffered rampant deforestation, largely unchecked since the 2021 military coup. In October 2024 alone, Myanmar lost more than 3.4 million hectares of forest, according to Global Forest Watch.

Between 2001 and 2023, Shan State, Tanintharyi, Kachin, Sagaing, and Karen accounted for over 9 million acres of forest loss.

“In Langkho, we had teak forests. Loilem had pine. Now, much of that has been turned into charcoal for export to Thailand,” said U Win Myo Thu. “The region is rich in coal, antimony, and gold. When Yagi hit, these bare hills couldn’t hold anything back.”

Gold Rush and Environmental Fallout

Gold mining has surged across eastern Shan State since the coup. A Thai government study linked landslides during the 2024 floods to aggressive gold mining upstream, especially near Mong Hsat.

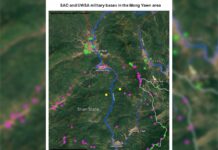

According to the Shan Human Rights Foundation (SHRF), the military has enabled mining operations in areas controlled by the United Wa State Army (UWSA) and Lahu militias, both aligned with the junta.

“Before the coup, there was no mining. Now machines dig into the hills day and night,” said Sai Kyaw, a resident of Mong Hsat.

These operations dump toxic waste, mercury, arsenic, and cyanide, into rivers, polluting farmland and wiping out aquatic life. Thai studies found zinc levels in the Mae Sai River up to 18 times the legal limit.

“When we were kids, the river was clear and full of fish,” said a Thai man in Mae Sai. “Now, it’s lifeless.”

The Resource Plunder

The Mae Sai River, which flows into the Mekong, is now heavily polluted. Meanwhile, military-linked firms are ramping up extraction across Shan State.

Since November 2021, the junta has issued mining licenses to over 300 companies. In southern Shan State alone, 132 companies extract coal, antimony, and iron; northern and eastern regions see operations for silver, lead, gold, manganese, and rare earths.

“This is just the legal side. Many more operate illegally,” said SHRF’s Sai Haw Hseng.

Revenue from these operations, often unregulated, helps prop up the junta, which previously relied on natural resources for up to 60% of its income.

Companies like Mayflower Mining, a military-crony firm notorious for environmental destruction, hold multiple permits. Locrian Precious Metals, led by Australian and Burmese investors, controls a gold exploration site spanning nearly 500 square kilometers near Tarlay Township.

“Only 20 companies in Mong Len are legal,” said Sai Haw Hseng. “More than 100 operate under the radar.”

Toxic Water, Silenced Voices

In Mong Phyak, Na Hai Long, and nearby villages, people once bathed in mountain streams. Now, their children suffer rashes, and the water runs brown with mining waste.

“Before, we played in the river. Now, it burns our skin,” said Nang Ut, a mother of two in Na Hai Long. “We have no choice. We can’t afford bottled water.”

Gold mining in the Loi Kyar area uses mercury and cyanide—chemicals often dumped untreated into waterways. Villagers say they fear long-term health effects but feel powerless to speak out.

In 2015, a local leader who opposed mining was assassinated. Since then, silence prevails. “If you speak out, you disappear,” said Nang Ut.

Profiteers and Secret Trade Routes

While communities suffer, minerals flow out across borders.

A trader in Tachileik told SHAN that Chinese buyers acquire gold and tin through networks tied to the UWSA. Most minerals exit via Mong La, Special Region 4, and on to China.

Manganese from Mong Koe is stockpiled near Tachileik Airport before crossing the border at Mae Sai. Thai Customs reported 135,000 tonnes, worth over USD 5.6 million, exported in 2019 alone.

From Mae Sai, the ore travels to Laem Chabang Port, and then by ship to China. Thai firms like SDiano hold export licenses, though many shipments remain underreported.

The Natural Resource Curse

Environmental expert U Win Myo Thu calls it a textbook case of the “natural resource curse.”

“The forests are gone, and now they’re digging up what’s left,” he said. “The people suffer floods, poisoned water, and disappearing livelihoods, while the profits go elsewhere.”

Villagers like Nang Ut feel forgotten: no compensation, no protection, and no future.

“If we keep living without laws, without a government that protects us, it will only get worse,” she said, gazing toward the river and the future with growing fear.

Leave a Comments