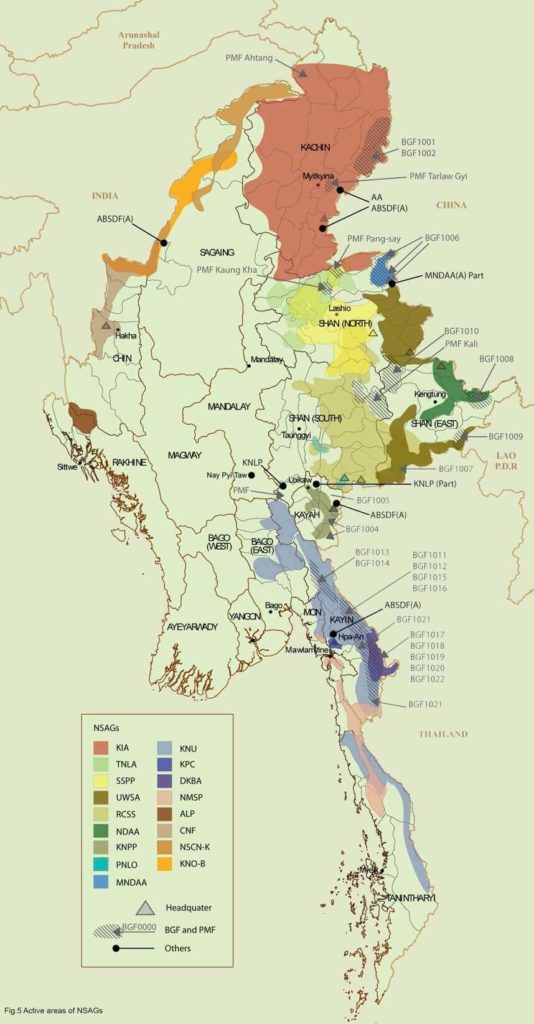

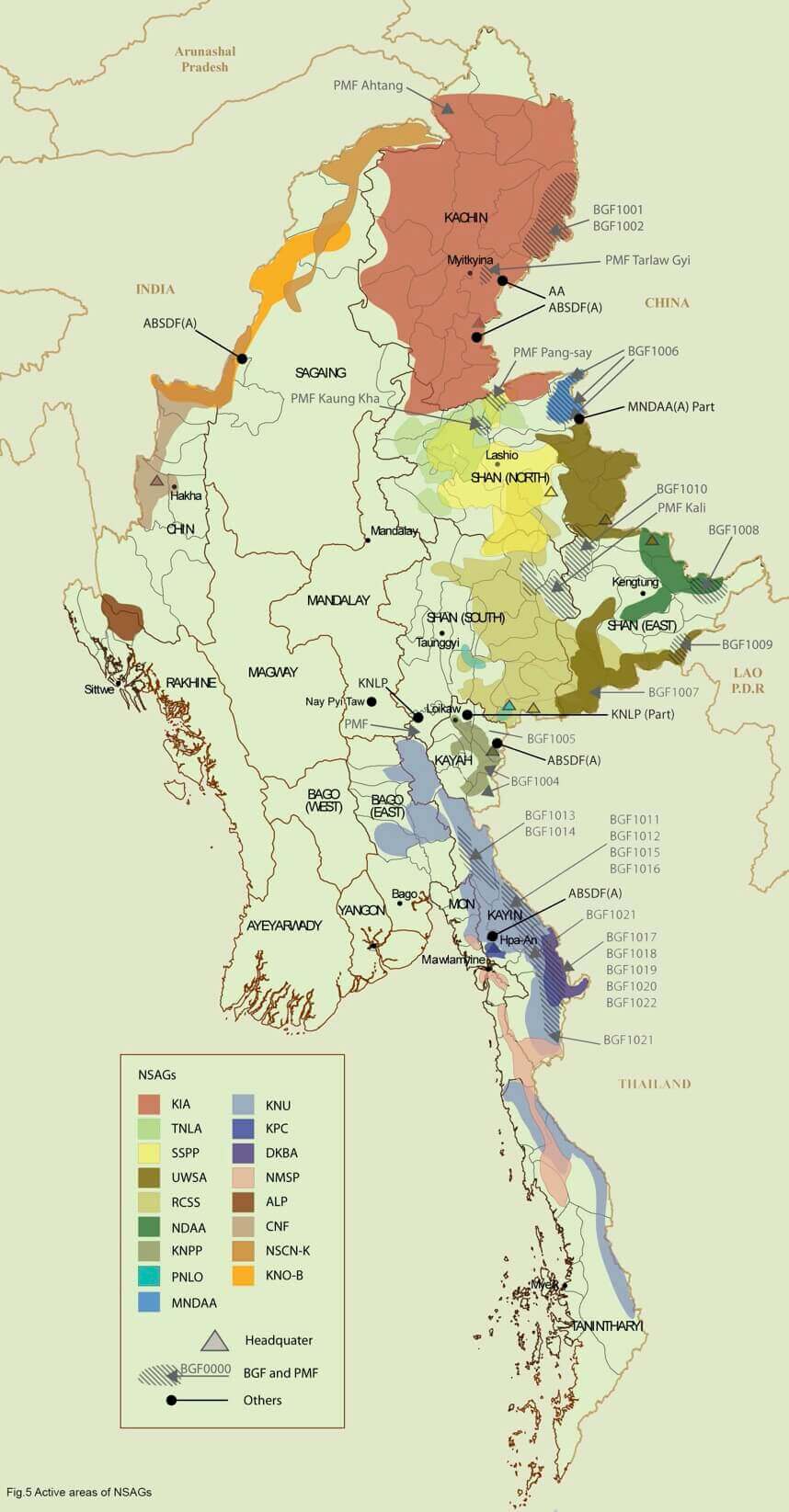

Finally, we are now at a stage to look into the territories controlled or operated by the ethnic armed organizations (EAOs), which cover contested areas, semi-liberated areas, and liberated areas.

In this respect, Kim Jolliffe in his “Ethnic Armed Conflict and Territorial Administration in Myanmar,” published by Asia Foundation, June 2015, outlined dozens of ethnic armed actors’ sub-national administration systems establishment that are not mandated by the 2008 Constitution. These overlap geographically with each other and with the administration systems of the state in many areas, including with the self-administered areas (SAAs).

The government official version is termed as Self-Administered Zones and Division (SAZ & SAD).

Accordingly, within Sagaing Region there is Naga Self-Administered Zone (Leshi, Lahe and Namyun Townships); within Shan State there are Palaung Self-Administered Zone (Namshan and Manton Townships); Kokang Self-Administered Zone (Konkyan and Laukkai Townships); Pa-O Self-Administered Zone (Hopong, Hshihseng and Pinlaung Townships); Danu Self-Administered Zone (Ywangan and Pindaya townships); and Wa Self-Administered Division (Hopang, Mongmao, Panwai, Pangsang, Naphan and Metman Townships)

In his report he mapped out or rather, specially invented terms for his study, which are “hostile claims, tolerated claims and accommodated claims”.

Accordingly, “the three main ways armed actors have gained control or influence over territories and populations: 1) “hostile claims”, where military force is used to seize or maintain access; 2) “tolerated claims”, where ceasefire conditions have led the Myanmar security forces informally permit access; and 3) “accommodated claims” where armed actors openly cooperate with the state in return for access. Very few of these territories have clearly agreed borders and those that do are rarely, if ever, formally documented.”

According to his report, such rebel administered territories with varying degrees of system are found in southeast of the country’s Karen State; South and East of Shan State; Kachin State and northern Shan State; northwest of the country in Sagaing Region including Chin and Arakan states, covering the southwest of the country.

Southeast Myanmar

After more than seven decades of ethnic armed conflict and the new ceasefire that followed since October 2015 Karen areas remain fragile, as do the resulting territorial arrangements, wrote the report.

The Karen National Union (KNU), Democratic Karen Benevolent Army (DKBA), and Tatmadaw and 13 Karen Border Guard Forces (BGFs) territorial claims overlaps in numerous areas.

The KNU system of governance is described by Kim Jolliffe as follows.

“At the crux of the KNU’s governance system are administrative committees for each of seven locally defined districts, 28 townships therein, and every village tract and village. These committees are each led by a chairperson, and are elected through congresses of representatives from the level below. As such, communities select village chairpersons, who then select representatives for village tract congresses. Village tract congresses then elect village tract chairpersons, who select representatives for township congresses and so on, up the hierarchy. These upwardly elected committees are thus instrumental in electing the organization’s leadership, and are also the primary administrative bodies, holding considerable executive power. The KNU’s armed wing, the Karen National Liberation Army, has automatic representation at each level too, but is subordinate to elected officials.”

“Further south, the New Mon State Party (NMSP) has controlled Mon State’s small border with Thailand and another patch of territory on the Mon-Kayin border with near total autonomy since its 1995 ceasefire with the government.”

“In Kayah State (also known as Karenni State, a term preferred by its people resistance armies) and neighboring Pekon Township in Shan State, the major ceasefire groups are the Karenni National Progressive Party (KNPP) and the smaller Kayan New Land Party (KNLP), while other territories are controlled or influenced by around half a dozen state-backed militia, including two BGFs.”

Thus, it could be said that KNU, NMSP, KNPP, Kayan New Land Party controlled areas fall under the category of “tolerated claims” while others are controlled by state-backed militia and BFGs which fall into territories with “accommodated claims”.

In Karen State, KNU administrate over Hpapun Township, Thandauggyi Township, eastern Hlaingbwe Township, eastern Kyaukkyi and Shwegyin Townships, Eastern Bago. DKBA over Eastern Myawaddy Township, Kyainseikgyi Township, Kayin State. Karen Peace Council over Kawkareik Township, Kayin State. All the three groups hold on territories fall into “tolerated claims”. But the BGFs 1011- 1023 rule over Hlaingbwe, Hpapun, Kawkereik, Myawaddy, Hpa-an and Kyainseikgyi Townships, Karen State are “accommodated claims” and even having a de facto influence on the territories, according to Kim Jolliffe.

Southern and Eastern Shan State

Likewise, in southern and eastern Shan State various EAOs come under different claims regarding their controlled territories, from “hostile, tolerated to accommodated”.

“The Pa-O National Organization (PNO) enjoys a high level of cooperation with the state, which has been augmented repeatedly since it signed a ceasefire in 1991. Its winning of all seats in the Pa-O SAZ as a formally registered political party has provided a new platform for working in an official government capacity. However, the extent of its ongoing influence remains largely dependent on its armed wing, the Pa-O National Army, which has formed a “People’s Militia Force” and maintains a robust parallel administration system of its own,” according to the report.

“In contrast, the administration system of the Restoration Council of Shan State (RCSS) is completely removed from that of the government. It was established through insurgency in rural Shan communities throughout the state, and has been only marginally tolerated by the Tatmadaw since a ceasefire was signed in 2011.”

Regarding how the RCSS administered its territories, the report wrote:

“The RCSS divides its area into five regions which it administers through around 20 “administrative battalions”. These administrative battalions are made up of soldiers with specialist training for administration and work alongside regular military “operations battalions”. These units have a degree of autonomy from the center, while the organization’s twelve other departments—for affairs such as revenue, education, and resource management—are based only at the central level and have to work with the local battalions in each area. The organization is currently undergoing a transition from a “wartime constitution” to a “ceasefire-time constitution”, the latter of which provides for greater participation of civilians.”

“The United Wa State Party (UWSP) has maintained a patchy presence along the Thai border since the state permitted it to attack Shan rebels in the late 1990s, and to oversee a mass migration of Wa civilians to the area.”

“In addition, the UWSP ally, the National Democratic Alliance Army (NDAA), known as the “Mongla Group”, has almost total autonomy along a significant portion of Shan East’s border with Laos and China. The political geography is further complicated by dozens of state-backed militia, including three BGFs, which have varied roles in governance.”

The relatively new Pa-O National Liberation Organization (PNLO) also has a small ceasefire territory in which it administers around 40–50 small mountain villages.

Thus, PNO and PNLO fall into the category of “accommodated claims”, while the RCSS would be more of a “hostile claims” in most of its operational areas mixed with “tolerated claims”, which are southern Mongton, Langkho and Mongpan Townships, and parts of Kengtung and Laikha Townships, Shan State. Other operational areas are parts of most townships in Shan (South) and Shan (East), east of Loilem and west of Kengtung. Also Namhkan, Kyaukme and Hsipaw Townships, Shan State (North) fall into its operational areas, which vary from time to time under “hostile” and “tolerated” claims.

United Wa State Army (UWSA) and NDAA or Mongla also fall into “tolerated claims”, with the former ruling over Wa-populated areas of southern Mongton, Monghsat, Langkho and Tachilek Townships, and the latter, Mongla Township, parts of Monyawng, Mongyang and Monphyak Townships, in Shan State.

Kachin State and Northern Shan State

Within the Kachin State and northern Shan State the following EAOs have base areas and operational areas.

They are Kachin Independence Organization/Army (KIO/KIA), Palaung State Liberation Front/ Ta’ang National Liberation Army (PSLF/TNLA), Myanmar National Democratic Alliance Army (MNDAA) or Kokang, Shan State Progress Party/Shan State Army (SSPP/SSA), UWSA and two known organizations called ceasefire groups New Democratic Army – Kachin (NDA-K) and Kachin Defense Army (KDA). While all fall into “tolerated claims” category, the ceasefire groups fall into the “accommodated claims”.

KIO rules over in much of eastern Waingmaw and Momauk townships. Parts of Tanai, Puta-O, Bhamo, Hpakan, Mogaung, and Mansi townships (Kachin State). Parts of Namtu, Kutkai, Hsenwi and Muse townships (Shan State), and, particularly after the decline of the PSLP/PSLA in 2005, Manton and Namhkan townships.

MNDAA rules over Konkyan, Laukkaing and the northern half Kunlong Township (north of the Nam Ting River).

SSPP administers in much of rural Lashio, Hsenwi, Namtu, Namhsan, Tangyan, Hsipaw and Kyaukme.

UWSA administers under the name of self-given “Wa State”, which is not endorsed by the government, the eastern Hopang Township, the whole of Mongmao, Pangwaung, Pangsang, Narphan townships and parts of Metman and Mongyang Townships.

NDA-K rules much of Tsawlaw and Chipwi Townships and the Kan Paik Ti area of Waingmaw (Kachin State).

KDA operates in part of northern and western Kutkai Township. But just a few months ago, the Tatmadaw has dissolved it because of suspicion over contact with government’s opposition armed groups in the area and reportedly, because of involvement in drugs trafficking.

TNLA is active in parts of Namhsan, Manton, Namhkan, Kutkai, Namtu, Hsipaw, Kyaukme, Mongmit, and Lashio Townships of Shan State, and Mogoke Township of Mandalay Region. In these areas, despite not holding any territories exclusively, the PSLF has been able to re-establish a basic administrative structure in hundreds of Ta’ang ethnic villages, according to Kim Jolliffe.

Western Myanmar

This portion of the country includes Sagaing Region, Chin and Arakan states.

In Sagaing area the National Socialist Council of Nagaland—Khaplang (NSCN-K) is active in the mountainous parts of Lay Shi, Hkamti, Nanyun, and Lahe Townships, while NSCN- Isak Muivah (NSCN-IM), another faction which mostly operates in India, also holds some territories on the Myanmar side of the border, in Lay Shi Township.

“Numerous Naga armed groups remain dominant in remote mountainous regions along Sagaing Region’s border with India, and administer the areas in accordance with traditional tribal systems that link communities to their own clan-like lineage through various hierarchical committees,” wrote Kim Jolliffe in his report.

“The ceasefire document provides the NSCN-K no official territory but states that ‘places agreed by both sides during the ceasefire’ were designated as areas in which weapons can be carried,” according to Kim Jolliffe report.

In Chin State, the Chin National Front (CNF) and government agreed through state-level and Union-level ceasefires {including the signing of the nationwide ceasefire agreement (NCA) in October 2015} that the armed group could establish bases and ‘move freely and without hindrance’ in ‘Tlangpi, Dawn and Zangtlang Village Tracts of Thantlang Township, and Zampi and Bukphir Village Tracts of Tedim Township’.

CNF has some 200 soldiers but never fought with the Myanmar Army.

In Arakan State the Arakan Liberation Party has a limited presence in northern Kyauk Taw Township but the organization has existed in its current form since the 1980s but appears to have never successfully controlled enough territory to instate stable systems of governance.

But since 2015 Arakan Army (AA), a new group formed in 2009 in Kachin State, entered Arakan State. By 2019 it has up the ante by attacking the security outposts in coordinated manner. The group has progress with leaps and bounds since its inception. It has started out with a few dozens recruits in Kachin State in KIO territory Laiza now said to be fielding more than 10,000 in Arakan State alone, according to conservative estimate.

“On 4 January 2019 – Myanmar’s Independence Day – the Arakan Army significantly intensified its insurgency, launching coordinated attacks on four police outposts in northern Rakhine State, killing thirteen officers and injuring nine others. The government directed the Tatmadaw to initiate “clearance operations” against the group, leading to a surge in troop numbers deployed in the state in an effort to “crush” the insurgency,” wrote the International Crisis Group (ICG) in its report “An Avoidable War: Politics and Armed Conflict in Myanmar’s Rakhine State,” on 9 June 2020.

“The Arakan Army’s continued strength is perhaps most evident from its ability to maintain its hold over most of remote Paletwa township in southern Chin State just over Rakhine State’s northern border (where it has rear support bases and training camps) and the Kaladan river, the key waterway connecting Paletwa to Kyauktaw and Mrauk-U in the Rakhine heartland. From this strategic area, it is able to project its authority deep into Rakhine State. At this point, the Arakan Army appears to exercise some degree of control over much of the rural center and north of the state. It also seems to have the ability to launch periodic attacks further south, apparently now as far as the southernmost township of Gwa.”

“The group now has effective control of the rural areas across much of central and northern Rakhine State and a large part of Paletwa. The village-tract authorities, the lowest level of the government’s administrative apparatus, either work for the group or feel compelled to report to it, and have little contact with the government administration in the towns.”

Analysis

Now let us look at the situation of the EAOs on how they fair under Kim Jolliffe categorization regarding their controlled areas.

Generally speaking all those EAOs that have signed the nationwide ceasefire Agreement (NCA), 8 under Thein Sein regime and another 2 more under the Aung San Suu Kyi-led NLD government, could be considered as “tolerated claims” category. But this is not to be so, as the main two strongest signatory EAOs, the KNU and RCSS repeatedly clashed with the Tatmadaw during the last two legislature period. All the rest small 8 signatory EAOs, some without armed soldiers and some with just a few hundreds, would fall into “accommodated claims”, because most are just waiting to compromise and will likely be satisfied with minimum political settlement.

Thus, the EAOs outside the NCA notably the Federal Political Negotiation and Consultative Committee (FPNCC) 7 members may be considered as “hostile claims”. But this is not the case, as the UWSA and NDAA fall into the category of “tolerated” and as well “accommodated” depending on how one looks at the given situation.

The two came into existence after the disintegration of the Communist Party Burma (CPB), when they were given territories to govern by the then military regime, together with the ceasefire agreement in 1989. UWSA and NDAA controlled areas which are also known as Wa’s Special Region 2 and Mong La’s Special Region 4.

Both groups have prospered economically dealing with China, although their way of earning might be disputable such as drug trafficking, running casinos, wild life trades, mining and so on, in cooperation with the people on the other side of the border, including provincial government of Yunan.

To the dismay of the Myanmar government both groups recruited thousands of soldiers and equipped them with modern weapons. Particularly, the UWSA is now said to have some 25,000 to 30,000 under arms but many speculate to be twice or thrice as much the estimation.

In short, the two areas of UWSA and NDAA are tolerated, accommodated and even have a de facto status of running their own administrations.

In contrast to the two, SSPP could be taken as tolerated claims in its areas of operation and headquarters, although at times, the Tatmadaw will launch attacks on its positions according to its wits and whims. And thus, a tolerated claims could become hostile at anytime. And as such, SSPP doesn’t have an accommodated status and quite far away from de facto position that UWSA and NDAA have been allotted with.

The KIA in the Kachin State and northern Shan State have, more or less, tolerated claims in many areas and hostile claims in many, particularly in northern Shan State, where it cooperates with the TNLA, MNDAA and AA under military alliance called Northern Alliance – Burma (NA-B).

Like the UWSA’s Panghsang town, KIO also has Laiza town at the Chinese border, which could be termed as liberated areas. Similarly Mai Ja Yang and Pa Jau, its old headquarters will also fall into liberated areas category.

Thus it could be said KIO has liberated de facto areas under its administration and pockets of semi-liberated to contested areas all through out Kachin and Shan State.

In the same vein, the late comer AA has also been able to assert it administrative machinery because the government has withdrawn many of the police outposts in remote areas. But at this writing there is still no concrete headquarters known that could be taken as liberated areas for the AA.

Now to come back to the secession urge of the EAOs, all have not publicly announced that they want to strive for secession and fight for total independence, although in the past almost all aimed for independence.

AA leader Tun Myat Naing has time and again made public that it admires the UWSA and would readily accept similar status and able to administer its own area. He termed this as confederation and thus could be argued as total independent countries coming together, which in end effect means also secession or total independence, depending on how one wants to term it.

But lately, with the disappointment on the NLD leadership and the Bamar-dominated military pinning their hope on maintaining their Bamar supremacy aspirations over other ethnic groups, many ethnic nationalities are questioning whether divorce or secession from Myanmar or Burma might be the only way out.

The cry for such separation and total independence is particularly high among exiles Kachin and Shan. And in turn, they are pressuring the real actors in the field, pointing at the example of the AA relentless, determined struggle against all odds.

So let us look at if such an aspiration is feasible.

Let us select out the Kachin, Shan and Arakan as possible candidates to strive for a new country.

Although declaring independence as a first step and becoming a state, according to declarative theory criteria won’t be a problem, achieving recognition, especially within the mold of UN will be an uphill, if not an impossible task.

Thus, the said three candidates will have to choose one of the following status, other than a full-fledged UN member nation. They are namely:

- Non-UN member states and observer states recognized by at least one UN member state

- Non-UN member states recognized by other non-UN member states only

- Non-UN member state not recognized by any state

First, can we achieve a status of like Vatican and Palestinian which is within the category of non-UN member states and observer states recognized by at least one UN member state?

Of course not, since we don’t have such stature and no country will back us up and the said two observer status states are intertwined with world politics and world consciousness which we don’t have and can’t lobby or claim to be as such. In short, our burden don’t loom large in international arena.

But are we in a position to become “Non-UN member states recognized by at least one UN member state, for examples like Kosovo, Taiwan, Western Sahara, Georgian breakaway states South Ossetia, Abkhazia, and Northern Cyprus. And the forcibly annexed Ukraine’s Crimea, and breakaway Donetsk and Luhansk, which Russia and only a few countries recognized. But still they are unable to become UN member nations.

In our situation, even though China has relationship with Kachin and Shan EAOs, notably through border check points of Kachin and Shan states, it is not going to give both states the level of recognition that Russia gave to the Georgian and Ukraine breakaway states.

This is because China is against disintegration of a sovereign nation-state and also it sees the national interest and economic opportunity where Myanmar is concerned as a whole and not fragmented units form, like the Russian did in Georgian and Ukraine.

The same is true for the Shan if it wants to lobby for Thailand’s recognition in case of independence declaration.

This makes us come to the last proposition of “Non-UN member state not recognized by any state.” And frankly speaking, there is no point to aim for such goals, as it won’t be bringing us anywhere to better our collective lives and fulfill our aspirations.

And as the world now works, a nation-state without UN recognition will be just a second rung countries with limited opportunity to grow and even to survive as a nation. Of course, Taiwan is a different story and it is still part of the Cold-War dispute left over that needs still to be settled.

In the same vein, AA’s aspirations will face the same hurdle, as recognition from either Bangladesh or India, which are its neighboring countries cannot be expected.

We all know that the creation of a new state needs the endorsement of the existing state, which means Myanmar has to agree with breaking away. For without its agreement we won’t be able to achieve recognition of other states, much less becoming a UN member state.

For now, the UN procedure isn’t in favor of new emerging nation-state or even state-nation. The international norms are contradictory and they are not even binding.

Of course, there as some instrument like humanitarian intervention, responsibility to protect (R2P) signed by most UN members but not binding in anyway, and so on. But all stop at the United Nations Security Council (UNSC) door, where the permanent five have absolute veto power, and with it the necessity of two third endorsement from the existing states to agree the dismemberment of a country is very remote. In short, territorial integrity and non-interference will be observed more than the rights of self-determination of the peoples.

To come back to the secession aspirations of the non-Bamar ethnic states, the present international setting is not in their favor. But this is not to say the situation will not change forever. Perhaps, there would be a place where such dispute of sovereignty and rights of self-determination could be settled. Somewhat similar to a world court, with sets of criterion vested with international law that would be enforceable, to do hearings on such cases and not everything has to stop at the UNSC door like it has been happening in today’s international politics.

But for now, even though the frustration may be high given the hopeless prevailing situation from two Bamar players – NLD and the Tatmadaw, the best bet for the ethnic nationalities will be to either aim for a higher degree of federalism, asymmetrical or symmetrical, or target at a confederacy in which the central will be given less power and more to the states. Of course, within the given boundary of Burma or Myanmar today.

Epilogue:

The conclusion part draws heavily from Kim Jolliffe’s “Ethnic Armed Conflict and Territorial Administration in Myanmar,” published by Asia Foundation, June 2015. His is the most extensive study on the EAOs administered areas to date, with the exception of AA’s control areas in Arakan State. For this part, ICG report of “An Avoidable War: Politics and Armed Conflict in Myanmar’s Rakhine State,” on 9 June 2020,” is quoted.

This piece of teaser is to arouse more study on Myanmar’s ethnic aspirations of rights to self-determination, especially from the point of secession or total independence, in relation to the existing world order and international norms.

Leave a Comments