Five years after the military coup, Myanmar’s junta is pushing ahead with an election widely viewed as illegitimate. With ongoing conflict across the country and no functional rule of law, the planned poll poses significant security risks to the public.

Activists and experts say the election will not be free or fair and is intended only to legitimize military rule.

IT experts warn that electronic voting machines, population databases (PSMS), and surveillance tools will allow the military to identify voters, non-voters, and critics. They say the data could be stored and used for long-term intelligence purposes.

As many governments and institutions have already rejected the plan, observers believe the election will heighten military tensions, increase public fear, and worsen Myanmar’s humanitarian crisis.

A Poll Without Democratic Conditions

Activists argue that public participation under threat of arrest is incompatible with democracy.

“The essence of democracy is the right to participate freely. Arresting those who disagree completely contradicts the meaning of democracy,”

— Nang Mwe, Shan youth activist

The Election Disruption Law enacted in July carries penalties up to the death sentence. It has already been used to punish online criticism of the election.

- 9 September: An IDP from Lashio, living in Aye Tharyar, Taunggyi, was sentenced to seven years of hard labor for a Facebook post.

- July–29 October: 88 people were prosecuted in 40 cases.

- First week of November: 22 more were arrested for sharing anti-election content or criticizing military propaganda films.

“People are being arrested simply for liking or sharing posts. This shows the military has no intention of holding a fair election,” Nang Mwe.

One day after announcing the election, the junta suspended key protections under the Law Protecting the Personal Freedom and Security of Citizens, further restricting movement and speech.

The Cyber Security Law, enacted on 30 July, criminalizes basic online communication, VPN use, and social media activity.

“There is no law punishing non-voters, but anyone who criticizes the election can be charged under the Cyber Security Law or other sections,”— Ko Htin Kyaw Aye, election monitor

Phased Elections Raise Security Concerns

At the NCA 10th Anniversary on 15 October, junta leader Min Aung Hlaing announced the election would be held in three phases beginning 28 December.

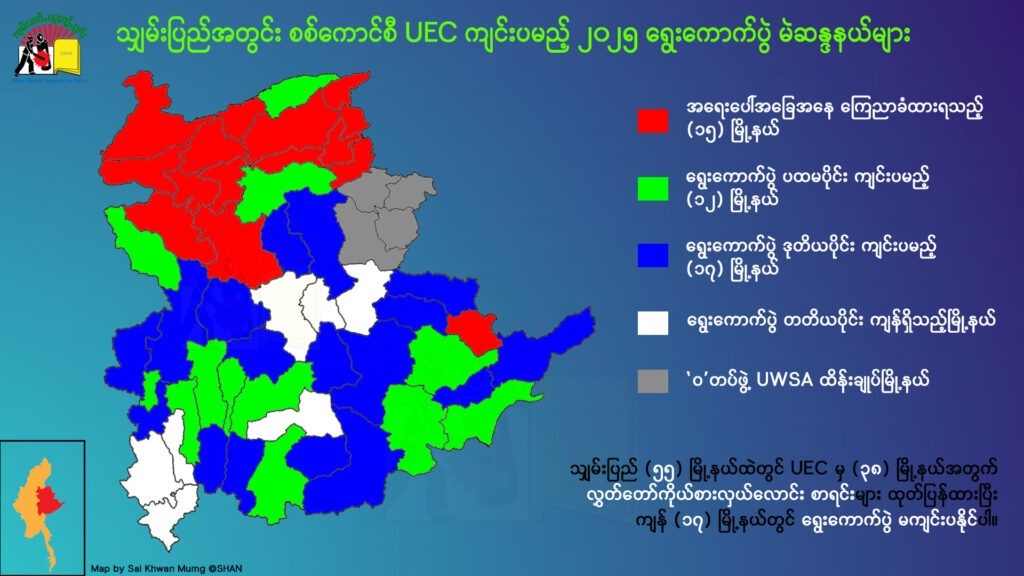

The UEC later released the township lists.

Phase 1 – 28 December 2025 (102 townships)

Townships in Shan State:

Nawnghkio, Lashio, Muse, Taunggyi, Hopong, Pindaya, Namsang, Linkhe, Loilen, Kengtung, Tachileik, Monghsat.

Phase 2 – 11 January 2026 (100 townships)

Townships in Shan State:

Tangyan, Mongyai, Ywangan, Hsihseng, Kalaw, Yawnghwe, Kunhing, Mong Pan, Mawk Mai, Mong Kung, Laihka, Mong Hkat, Mong Peng, Mong Hpyak, Mong Ton, Mong Yawng, Mong Yang.

Phase 3 – Expected 25 January 2026 (72 townships)

Townships likely included:

Kyaukme, Hsipaw, Pang Laung, Paikhun (Pekon), Yawng Hwe, Mong Nai, Keng Tawng, Monghsu, Mat Man.

Out of 55 townships in Shan State, the UEC has announced candidate lists for only 38.

On 14 September, the UEC said elections would not be held in 17 townships under the control of ethnic armed groups, including areas of the UWSA, NDAA, KIA, TNLA, and MNDAA.

“The phased approach shows they cannot control the country. It allows manipulation and pressure on voters,” Ko Htin Kyaw Aye.

Under the State of Emergency, civilians and candidates have no protection.

“Anyone can be arrested or followed at any time,” he said.

IDPs Face Pressure and Security Risks

Intensified clashes in Northern Shan and Karenni State have displaced tens of thousands into Southern Shan. Aid workers say the military is now forcing IDPs to return home, even to unsafe areas affected by fire, landmines, and active fighting.

“They push people back so they can claim the area is stable for an election,” Nang Hla Khin, IDP relief worker.

In Muse Township, immigration officers have been issuing new household lists and updating voter rolls since May.

A Lashio legal expert warns that the process exposes civilians: “Once you provide your data, they know your address, who voted, and who did not. People fear being arrested or conscripted.”

Since the People’s Military Service Law came into effect in February 2024, many young people have fled to liberated areas or abroad.

Experts also warn that electronic voting and the PSMS database enable extensive surveillance.

Fears of Conflict During Voting

Ethnic armed organizations have released statements rejecting the junta’s election, raising fears of clashes and instability around polling sites.

Residents worry about:

- attacks on polling stations

- bombings or ambushes

- mass arrests

- forced voting

- sudden conflict in populated areas

“No one can guarantee there will be no fighting during voting. Public security is the main concern,” Lashio legal expert.

Election monitors say many people may feel forced to vote due to surveillance and arrests.

“People may feel they have no choice. Violations must be documented,” Ko Htin Kyaw Aye.

The UN IIMM said on 26 November that reports of serious international crimes—including the arrest of children over anti-election leaflets—are increasing.

International Community Rejects the Poll

Myanmar’s pro-democracy bodies—the NUG, CRPH, and NUCC—have urged the world not to recognize the junta’s election.

International organizations have responded:

- ASEAN: Will not send observers

- EU: Says no credible result can be expected

- UN Secretary-General António Guterres: Called it a “sham election intended to legitimize military rule”

The junta says Russia, China, India, and Thailand provided election technology.

Shan political figure Sao Harn Yawnghwe says the planned poll has no link to democratic principles.

“An election without freedom reflects only the will of the organizers. This election has no connection to democracy.”

Analysts say the election process remains disconnected from the public will.

“There is war everywhere and no rule of law. Even after this election, nothing will improve for the people,” Nang Mwe.

This report was originally published in SHAN’s Burmese section.

Written by Sai Khwan Murng, co-written by Sai Harn Lin, and translated into English by Eugene.

Leave a Comments