By Pippa Curwen

Thursday, April 9, 2020

On March 2 this year, for the first time, the decades-old disappearance of Shan prince Sao Kya Seng was commemorated in Hsipaw by a group of local youth, who organized a vigil at his family’s cemetery outside the town.

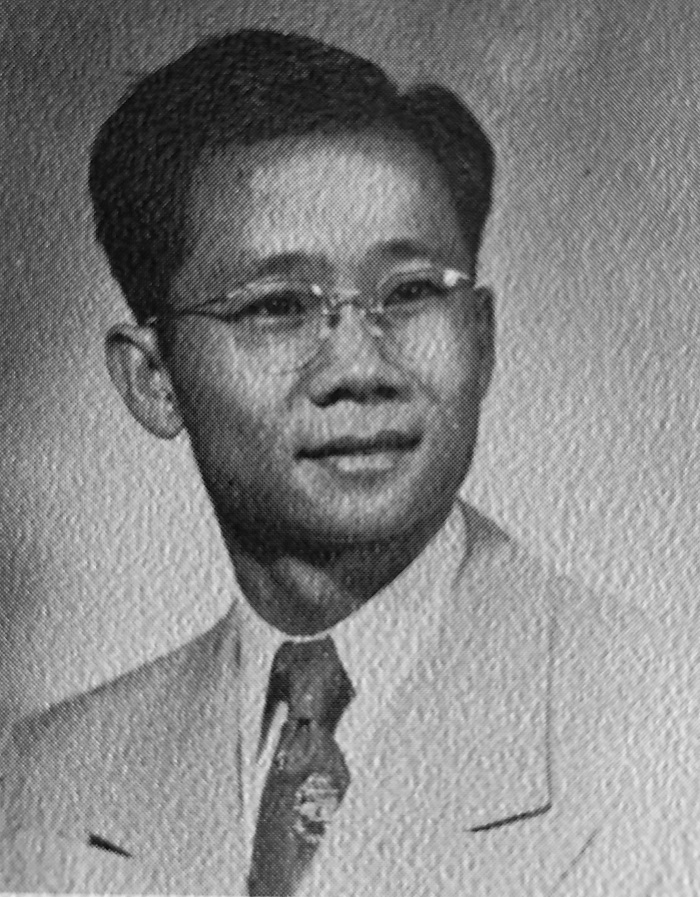

Underneath the concrete, domed structure sheltering the largest of the tombs, sombre mourners placed lit candles and white roses beside a photo of the bespectacled prince. Underneath, a handwritten poster demanded: “It’s been 58 years since Sao Kya Seng was killed. Where is truth? Where is justice?”

The 38-year-old prince was arrested outside Taunggyi on the day of the army coup in 1962, taken to the nearby Ba Htoo Myo military camp, and never seen again. The military later denied ever having arrested him.

“We want to find his remains, bring them to this cemetery and erect a memorial for him,” said Hsipaw resident Nang Than Nu at the ceremony.

While the prince’s disappearance is no longer a taboo subject in Burma — copies of his Austrian-born widow Inge Sargent’s autobiography “Twilight over Burma” are now sold openly – it still touches a raw nerve with the authorities. The film adaptation of the book was banned in Yangon five years ago, and to this day the Burmese government has never replied to letters sent by his daughters each year, asking what happened to their father.

The organizers were thus taking a risk in holding the event. Clues as to why can be found in the memorial invitation, which states that Sao Kya Seng disappeared while “striving for federalism and the Shan cause.”

Sao Kya Seng was well-known for his efforts to modernize and develop Hsipaw – returning land to farmers, rooting out corruption, and promoting local education and healthcare — and for opposing Burmese military expansion in Shan State. His refusal to raise funds for the military, and to accede to a humiliating demand by army chief General Ne Win to wait at the roadside to greet him as he passed through Hsipaw, likely sealed his fate.

Committed to democratic processes, Sao Kya Seng had sought federal reform through parliamentary means. He attended the seminar held for this purpose by Prime Minister U Nu in Rangoon in early 1962 – the very meeting used as a pretext for the coup by General Ne Win, who accused ethnic leaders of plotting the nation’s disintegration. By ill chance, Sao Kya Seng had returned early to Shan State due to a family illness, enabling the military to arrest him away from the public eye. Other Shan leaders arrested in Yangon served prison sentences in Insein Jail.

Sao Kya Seng’s dreams of federalism clearly resonate strongly with Hsipaw youth today. Their demands for answers to his disappearance are thus as much about wanting justice as about reviving his federal aspirations, crushed on the fateful day of the coup nearly six decades ago.

It appears no coincidence that the memorial was held this year — the fifth and final year of the current government’s term — when the NLD’s promises of federal reform and peace have proven definitively empty.

For Hsipaw has seen little tangible benefit from the past decade of purported democratic reform — only escalated war and accelerated exploitation of its lands and natural resources by military and business elites.

The Burmese military’s breaking of decades-long ceasefires in 2011 displaced tens of thousands in northern Shan State, setting a grim pattern of dislocation and suffering that continues in Hsipaw until today.

Likewise, the laying of China’s oil and gas pipelines across Hsipaw eight years ago — cleaving an ugly gash through the bucolic valley — set the pattern for development in the area: top-down, benefitting distant elites, and oblivious to the needs and wishes of local communities.

Residents of Baw Gyo, a traditional salt well area west of Hsipaw town, tried to block the laying of pipelines through their lands, fearful that salt corrosion might cause leakage or explosion. Their concerns were ignored and the giant pipes laid just 100 meters from the historic Baw Gyo Pagoda, one of the holiest sites of Shan Buddhism.

Compensation for farmers impacted by the pipelines was uneven and riddled with corruption. The only income available to locals today from the multi-billion dollar project is a mere 300,000 kyat (200 US dollars) a month, earned by labourers walking six kilometers a day to clear bushes along the pipeline route.

Hsipaw residents live in dread of far greater disruption if the planned China-Myanmar Economic Corridor goes ahead, with a giant highway and high-speed rail slated to pass directly through their valley.

The extractive free-for-all taking place in Hsipaw today is a far cry from the sustainable mining envisioned by Sao Kya Seng, who had trained as a mining engineer. Environmental protection laws, where they exist, have been systematically ignored by coal and cement mining companies, leaving farms and forests gutted, waterways poisoned, and the air choked with dust.

Army deployment to secure the Nam Ma coal mines in southeast Hsipaw has led to arbitrary arrest, torture and killing of civilians.

And now Hsipaw’s very artery, the iconic Namtu River, is under threat from hydropower dams being built above and below the town. The giant Upper Yeywa dam will submerge vast tracts of fertile farmland, growing the famously sweet oranges which Sao Kya Seng dreamed of turning into an agricultural staple of his state.

Unanimous local opposition to the Upper Yeywa dam has been ignored, not just by the Naypyidaw government, but by foreign investors. The Swiss government even made sure that Shan resistance leaders, invited to Switzerland on a “peace-building” exposure trip in 2016, were toured around hydropower projects by the Swiss company Stucky, which is building the Upper Yeywa dam.

When elected Shan lawmakers tried to block the budget for the Upper Yeywa dam in the Naypyidaw parliament two years ago, they were voted down resoundingly by 501 to 28 – revealing the futility of trying to protect local ethnic interests under the current constitution.

One of these frustrated lawmakers, Hsipaw MP Nang San San Aye, joined the memorial ceremony on March 2.

“We want people to know we had our own Shan rulers in the past. We want to restore our Shan heritage,” the youthful MP explained.

For decades of centralized Burmese rule and assimilation have eroded the Shan cultural identity, and with it an awareness of historical Shan self-rule.

This memory loss is no accident. Just as the Hsipaw rulers’ tombs have been left rundown and neglected, their grand summer palace Sakandar, damaged since World War Two, has been left in ruins – a stark contrast to the larger-than-life statues of former Burmese kings in Naypyidaw, and the painstaking restoration of their ancient palaces.

Frustration with systemic marginalization and injustice is clearly simmering among Shan youth. At the memorial ceremony, someone had scrawled angrily on a piece of cloth: “Down with racial hegemony! Down with military dictatorship!”

As the people of Hsipaw brace for the coming pandemic, with a chronically under-resourced health system and increased military repression in the “national” interest, this anger is surely only going to grow.

Leave a Comments