On February 20, the Lower House debated the Union Election Commission’s (UEC) to change in the UEC’s proposal to stipulate a residency requirement of at least 90 days in order to participate in the voting for the upcoming 2020 national election, which was approved. The UEC originally even proposed a requirement of less than 90 days. Accordingly, the required change will become law if it is approved by the Upper House.

The United Nationalities Alliance (UNA) on February 24 issued a five-point statement rejecting the proposed change of regulation arguing that it will intrude and upset the rights of local people self-determination rights unnecessarily.

The statement also argued that the 180 days regulation that has been in place is working and besides there are other mechanism such as like advance voting for Myanmar foreign residents, which could be more appropriate and easier if the UEC wants to enhance the voting rights of all citizens. Altering the rule to benefit a party or individual is not a correct way to do.

Besides, there could be argument in preparing the voting list between the local people and the authorities who are doing the preparation. And finally distrustfulness could occur, due to local’s people rights to express their wishes (unnecessarily altering the voting pattern by outside voters) and disrupt ethnic unity.

The problem has always existed regarding the Bamar-dominated political parties fielding candidates in ethnic states, such as the ruling National League for Democracy (NLD) and the opposition Union Solidarity and Development Party (USDP).

While the two Bamar parties like to portray themselves as national parties, cutting across ethnic lines, the non-Bamar ethnic nationalities have never accepted them as such. Thus, their competing in ethnic states is seen as intrusion of their rights from the outset, which they consider should only be decided by themselves. The collaboration of some locals as members to the two parties are even seen as being disloyal by the ethnic local people, even though they are powerless to do anything against it.

It is, of course, understandable that the ethnic parties worry the proposed amendment will further erode their voter bases and they see it as an attempt to win more parliamentary seats in the ethnic states, notably the NLD which is doing everything to collect more votes in their homesteads.

In the same vein of undertaking military members and their families will have to vote at polling stations outside of their barracks in this year’s general elections after the MPs, with NLD majority casting the votes, passed amendments to election by-laws on February 20. Perhaps NLD reasoned that the military members might have more liberty on how they vote, if it is done outside the military decision-makers’ influence of their subject, which actually is often the case.

Moreover, the ethnic parties are of the opinion that since the main reason of migrant workers for moving into ethnic states is to work, they should as well return to their home constituencies to vote.

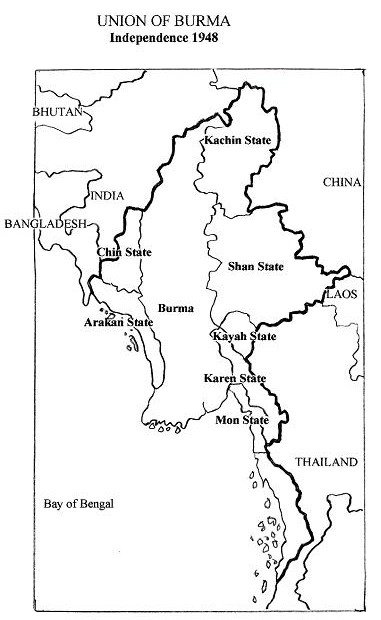

The ideal scenario for 2020 election would be to leave the ethnic states’ population compete among themselves to choose their own representatives and the Bamar parties only contest the elections only in divisions or regions among themselves, like in 1947 Burma’s election which followed after the signing of Panglong Agreement in 1947.

On 9 April 1947, on the eve of achieving their independence from British colonial control, the Anti-Fascist People’s Freedom League (AFPFL) led by national hero Aung San won the first ever elections, in Burma Proper or Ministerial Burma excluding Frontier Areas, which were Kachin, Chin Hills and Federated Shan States. On 19 July 1947 Aung and many of his cabinet members were gunned down which now is being commemorated as Martyrs’ Day.

The thinking out aloud of such a scenario is because Burma or Myanmar today isn’t a country that can be considered as post-independence or rather post-war country, given that some 80,000 of ethnic armed organizations (EAOs) pitting against Burma army or Tatmadaw, which fields some 350,000 troops.

And as almost all non-Bamar EAOs, some 20 of them, are against the Tatmadaw and the civil war dragging for seven decades without foreseeable end in sight, a remaking of the political setup would do everyone good.

As such, going back to the pre-Panglong Agreement period will be a way out of this deadlock or political muddling through for decades. Subsequently the Bamar can sort it out among themselves the party that should be their representatives and likewise, the non-Bamar ethnic nationalities could also do the same.

After this, the Bamar and ethnic representatives could again meet in a kind of Panglong setting of 1947 anew and determine the political course of the country.

This way, all of us will be spared of having to muddle through again, which we have been doing for decades without achieving reconciliation, harmony and political settlement, but only straddled with the ongoing civil war.

Leave a Comments