On June 26, the 32nd International Day against Drug Abuse and Illicit Trafficking, narcotics seized in 2018 were destroyed in three cities in Myanmar. The seized narcotics from northern Myanmar surpassed last year’s amount, according to the authorities.

Government sources said illegal drugs confiscated within the 2018-2019 period burned all over Myanmar in public view in Yangon, Mandalay and Taunggyi totalled an estimated value at K451,746.37742 million (approx. US$301.1642517 million).

Reportedly 24 kinds of drugs were burned, including heroin and amphetamine, last year. This year, 32 kinds of drugs were destroyed, including heroin, methamphetamine, ice and pseudoephedrine, worth millions of US dollars.

Similarly, the bonfire also took place in Mongla’s National Democratic Alliance Army (NDAA) headquarters, at the same date, presided over by its leader Sai Lin and his top lieutenants where some 1000 kilograms of narcotics worth US$8 million which included crystal ice, heroin, opium and 5950 kilograms drugs precursors were burned, according to the report of The Irrawaddy.

In the same vein, drugs burning bonfires were also held in Restoration Council of Shan State’s (RCSS) controlled areas of Mongpan, Mongkung, Kengtung, Mongnai, Mongton and Homong townships, which were attended by RCSS authorities and Sanghas (Monks) of the respective townships. Awareness-building on the danger of using drugs were also said to be carried out by the RCSS, reported by Shan sources.

On the occasion, president Win Myint at the Myanmar International Convention Centre 2 in Naypyitaw also told the audience in his speech: “Illicit drugs can break down health and social fabrics, and the basic economy of the people and link to terrorist activities, money laundering, illicit financial flows, bribery and corruption and transnational crimes in the country. Profits generated from illicit drugs trade can also breed armed insurgencies and terrorist activities.”

Linkage of drugs and money laundry

On the same occasion regarding the drugs issue, Maung Maung Kyaw, director general of the Ministry of Home Affairs’ Bureau of Special Investigation told the media that 90 percent of the money laundering cases his bureau investigates are tied to drugs.

The bureau leads international money laundering investigations in partnership with the Central Bank of Myanmar, the Income and Revenue Department, the Department of Agricultural Land Management and Statistics, the Customs Department, the Financial Investigation Police Force, the Anti-Narcotic Task Force and the Anti-Human Trafficking Police Force, and they partner on information sharing with their counterparts in Thailand.

Thus when the issue of money laundry is touched, it is impossible to pursue the case without going into narcotics trafficking. This leads us to look into the drugs related scenarios and its ramification.

Northern Shan state political economy

Shan State’s armed conflict has always been intertwined with drug trade since 1950, as the recent International Crisis Group’s (ICG) January 2019 report has rightly pointed out. Shan state has long been a global centre of illegal drug production and for decades was the primary global source of opium and heroin until Afghanistan took over in the 1990s. But it is now the centre of a massive methamphetamine manufacturing and trafficking business, linked to sophisticated transnational criminal organisations.

The drug trade was brought in by the Kuomingtang (KMT) when in 1949, its remnants of the nationalist Chinese Kuomintang Army fled China in the face of Communist victory and invaded Shan state establishing a series of base areas in eastern Shan state along the border with Thailand.

“Necessity knows no law. That is why we deal with opium. We have to continue to fight the evil of communism, and to fight you must have an army, and an army must have guns, and to buy guns you must have money. In these mountains, the only money is opium,” said the KMT commander General Tuan Shi-wen in 1967, according to “US Foreign Policy and the War on Drugs: Displacing the Cocaine and Heroin Industry” written by Cornelius Friesendorf.

Since then the argumentation seems to become the moral operation code in relation to the armed conflict and the organizations involved within Shan state that almost immediately followed after Myanmar’s independence from the British in 1948.

From those early days, the shape of drug production and trafficking have changed from raw opium to heroin, methamphetamine, ecstasy and now to high grade refined crystal ice. But the main stay of reliance on drug trade to finance insurgency as a main source of revenue remains in tact and undisturbed, so also the maintenance and control of the individual EAO’s territories.

Drug production and profits are now so vast that they dwarf the formal sector of Shan state and are at the centre of its political economy. Experts estimate that the total value of the drug trade at over US$ 40 billion per year which is increasing rapidly.

Actors and tradition

Those involve in this political economy drug trade are a “chain of actors from the Tatmadaw, to larger militia units involved in production, to smaller militias subcontracted to provide localised security, and the armed organisations that levy taxes on the trade all benefit and receive due compensation,” according to the ICG report. In other words, a multiplicity of armed actors are involved.

In spite of this northern Shan state is being spared from bloodshed that blighted the Colombian city of Medellin during the heyday of cartel activity in the 1990s or, until recently, Ciudad Juarez, on the Mexico-U.S. border or other Mexican cities, stemming directly from rivalry in drug trade, although it has a fair share of inter-ethnic armed conflicts which are not directly related to it.

“The answer lies in the fact that the intersection of armed conflict and the illicit economy in northern Shan has for decades operated as “an economic-commercial world of interdependent, entrepreneurial patron-client clusters”, that is geared toward avoiding fighting as much as practicable around economic ventures such as drugs,” wrote the ICG report.

The drug trade in northern Shan State is observed by one experienced observer as: “It is a cooperative system. There is no single controller. It is different from when it was under the control of Lo Hsing Han or Khun Sa”.

Now it is increasingly becoming professionalized, dominated by transnational criminal syndicates operating at huge scale.

Money laundry

Myanmar spent almost five years on the black list from June 2011 until it was moved to the grey list on 19 February 2016. And again, removed from gray list on June 24 the same year.

The decision came after an on-site visit from a Financial Action Task Force (FATF) team, which counts China, the United States and India as members, to determine whether Myanmar was making sufficient progress with recommended reforms. Those reforms included criminalising terrorist financing, freezing terrorist assets and ensuring Myanmar’s financial intelligence unit was “operationally independent,” according to the Myanmar Times report.

While freedom from the list should mean other countries and their financial institutions now find it easier to do business with Myanmar, quite a lot regarding corruption, tax evasion and so on of the companies still have to be tangled. But chief among them will be on how to rein in on the Ethnic Armed Organizations (EAOs) that operate independently from central government’s sway and of course, the multitude of militias and Border Guard Force (BGF) units that are intertwined with the Tatmadaw and have been part and parcel of the drug economy, directly or indirectly, sometimes taking directives from above and at times out of sheer personal greed and individual necessities.

While disbanding the militias and BFG units involvement might be manageable, if the government choose to cut the loose of its subordinates dependency on drug trade, EAOs running their own fiefdoms as independent entities will be problematic.

Thus, from money laundry point of view, it is not a wonder that Myanmar is not much or seriously interested as an assessment of a recent report by Asia/Pacific Group on Money Laundering (APG) of 2018, titled “Anti-money laundering and counter-terrorist financing measures – Myanmar, Third Round Mutual Evaluation Report,” wrote: “Myanmar is exposed to a large number of very significant ML (money laundering) threat. Higher risk predicate offences include drug production and trafficking, environmental crimes (including illegal resource extraction (jade), wildlife smuggling and illegal logging), human trafficking, corruption and bribery. There are complex contextual issues that increase Myanmar’s risk profile, including significant areas of the country controlled by non-state actors and characterised by very serious threats from transnational profit driven crime trends and related ML.”

The report’s key findings second paragraph said: “Most relevant authorities demonstrate a reasonable understanding of TF (counter-terrorist financing) risks, but do not demonstrate a credible understanding of Myanmar’s much more serious ML risks.”

In its key findings closing it wrote: “Myanmar does not pursue international cooperation as priority or in a way that that is in keeping with its risk profile. There is no clear commitment or practice to pursue MLA (money laundering activities). Myanmar makes some use of cooperation, especially with China and Thailand along shared borders, but this is fundamentally lacking when considering Myanmar’s overall risk profile.”

On June 28 in Naypyitaw in a bit to show the country’s earnest commitment anti-money laundering central team joint secretary police brigadier general Kyaw Win Thein said his team was closely watching and monitoring money laundering and terror funding in the country in order to prevent potential terror attacks.

He added that they had been closely monitoring and watching terror funding for over three years to check illegal drug trafficking within the Arakan state.

Gun-running

The major source of EAOs’ armament comes from China, with Thailand and Cambodia to a lesser extent.

The Chinese arming of the Communist Party Burma (CBP) in mid-1960s to mid-1980s, even after its disintegration continues, albeit in a different way. While the arming of CBP was free of charge delivery for its ideological comrades-in-arms, the ethnic armies born out of CPB such as Myanmar National Democratic Alliance Army (MNDAA), United Wa State Army (UWSA) and NDAA were of give-and-take nature with the Chinese business organizations mostly based in Yunan province of China adjacent to Myanmar.

But soon, apart from just being a reseller of arms, the UWSA began to manufacture its own weapons and ammunition, that its also sold them to various EAOs and even as far as to the Indian insurgents like the National Socialist Council of Nagaland (NSCN) and its allies. The National Democratic Army – Kachin (NDA-K), known as Kachin special region 1, which has now become BGF, was also pointed out by Indian media sources as an exporter of its weapons, which were made in its factory copied from the Chinese models. The Kachin Independence Army (KIA) also has its arms factories which it sold to the various EAOs, probably also to the Indian insurgents.

The range of war weapons produced by the UWSA include replicas of the Chinese-designed M–22 assault rifle, and the Chinese M–23 light machine gun, as well as 7.62 mm ammunition that is used by both weapons. Chinese technicians are invited to provide advanced training in the production of artillery and other weapons. Informed sources said the Wa now produces 122-mm howitzers in their own factories.

The Wa weapon factories are said to be operational since September 2006. However, Burma expert Bertil Lintner said that in 2010 the Chinese asked the UWSA to close down the factory in Kunma not far from Panghsang as it was becoming an embarrassment. But it is not clear if the UWSA has moved its factories across the border in a joint-venture form with the Chinese manufacturers on Chinese soil or have located to a new unknown place within its jurisdiction.

The KIA also produced a range of weapons including Type 81 variants dubbed the M23, sniper rifles, grenades and ammunition. The factories were run by the Chinese specialist but it took over in 2015. It has surely armed the TNLA in its initial revamping of its forces and as is usual with the EAOs, selling weapons to other outfits cannot be ruled out.

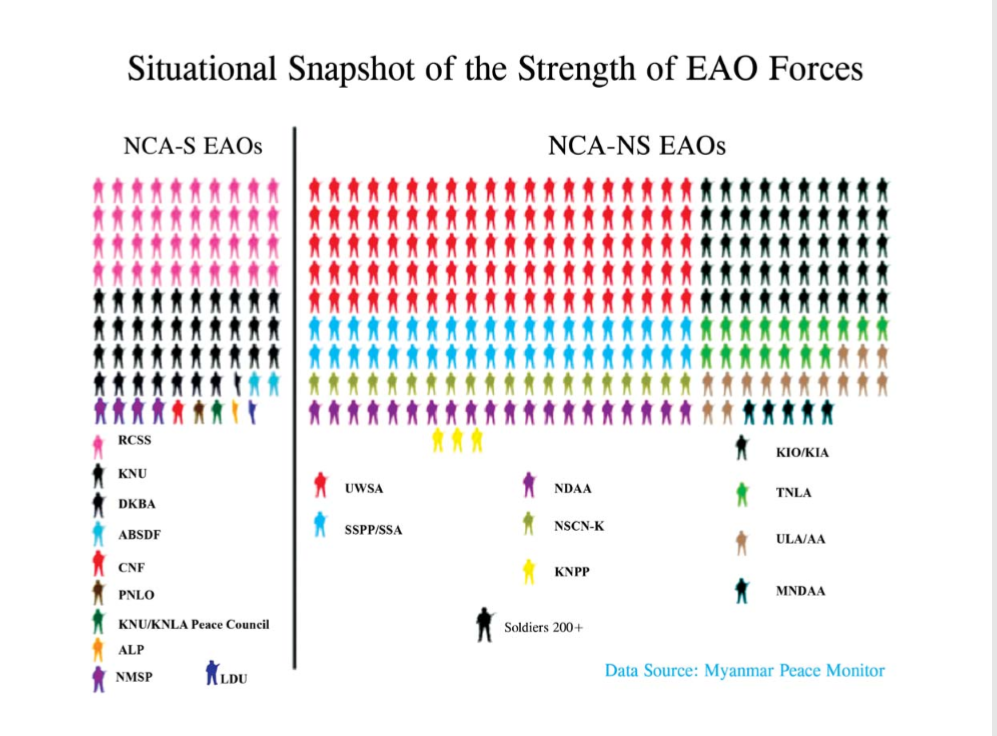

And with EAOs fielding some 70,000 troops, weapon demands are high and gun-running is no doubt a lucrative industry. No wonder that the UWSA, KIA and even NDAK are in business. Now even the TNLA and MNDAA are also said to be eyeing to set up arms factories with the proceed of some 73 million US$ that the MNDAA and TNLA gained from raiding the casino in Laukkai run by the Pansay militia in Kokang’s Laukai in March 2017.

Perspectives

Given such linkage between drug trade, money laundry and gun-running the political economy involves not only Shan state but also the whole of Burma and regional capitals that are drawn into narcotics export markets.

As mentioned earlier, Myanmar faces an uphill battle in getting rid of the drug menace and money laundry that comes with it. Exacerbating the situation further is the domestic weapon selling, export and war weapon proliferation, which fall into the category of counter-financing of terrorism.

Myanmar Financial Intelligence Unit (MFIU) serves as the central agency to receive, request and analyse the reports submitted relating to money laundering, financing of terrorism, or any predicate offences. Its objectives are stated as money laundering, predicate offences related to money laundering and to prevent subsequent offences. Moreover, it aims are to prevent proliferation financing of weapons of mass destructions and freeze the assets.

The question to be asked is how are the authorities going to discharge such given duties with respect to Kachin Laiza, UWSA and Mongla areas which are run independently without Myanmar government’s interference as separate political units for decades since 1989?

Further, the EAOs mostly invest their gains in either Panghsang the Wa capital or Mongla the NDAA headquarters bustling with casinos, mineral extractions, banana and rubber tree plantations, real estate development and infrastructure undertakings, where Chinese entrepreneurs also have stakes in the businesses. Besides, although UWSA was known to invest quite massively within Myanmar until 2009 when government pressed for all EAOs to convert into BGF scheme and come under its military, which most rejected, it is now said to invest mostly in China, with Mongla also following suit.

Last but not least, how is the MFIU going to fare if it is to investigate the UWSA money laundry activities which are supposed to be done at Kings Romans Casino, according to a CNN report titled “Asia’s Meth Boom” of 5 November 2018 ?

The place is run by Hong Kong-based Kings Romans International (HK) Co. Ltd. on a 102-sq-km (39-sq-mile) special economic zone that occupies seven km of prime Mekong riverbank overlooking Myanmar and Thailand. The casino is part of the Bokea Special Economic Zone (SEZ) in northern Laos where the Chinese are investing a lot of money for tax-free development. Projects in the SEZ are granted a 99 year lease, at the end of which all properties are to be ceded to the Laotian government.

As such, the undertaking of anti-money laundry and counter-financing of terrorism, including gun-running will be tasks that are nearly impossible to resolve or come to grips with just piecemeal instrument of anti-money laundering law, as only political settlement with the multitude of EAOs would be able to do the comprehensive job.

Leave a Comments