It is interesting to consider whether the autonomy claim of the National Democratic Alliance Army (NDAA), also known as the Mong La group, has anything to do with the Shan unity.

.

Long before the 2010 transition to democracy in Myanmar, the Mong La group demanded autonomy from the central government. It seems, however, that the demand for autonomy brought out by the Mong La group has little to do with the unification of the Shan. Several efforts at Shan unity have been made. The most recent came in 2013 when Shan organizations founded the Committee for Shan State Unity (CSSU), which aims to encourage Shan unity by bringing together political parties, civic organizations, and armed forces.

Prominent Shan organizations joined the coalition which include the Shan State Joint Action Committee (a coalition of Shan Nationalities League for Democracy, Shan State Progress Party/Shan State Army, and Shan State Militia Force); Shan Nationalities Democratic Party (SNDP); Restoration Council of Shan State/ Shan State Army (RCSS/SSA); Shan Community Based Organizations; Tai Youth Organization; Shan Lawyers Network; New Generation Shan State; Tai National Association Thailand; Eastern Shan State Development and Democratic Party (ESSDDP); and Tai Youth Network (TYN). The Mong La group is however absent.

The CSSU has 12 guiding principles that demonstrate the organization’s dedication to decentralized government, equality among Shan State nations, human rights, and financial autonomy. However, since its founding in October 2013, the CSSU has encountered difficulties in attaining its goals, which may be attributable to divisions among Shan organizations. Both the SSPP/SSA and RCSS/SSA are members of the CSSU, but they have engaged in armed conflict with one another, undermining the credibility of the alliance. This resulted in displacement and distress among Shan villagers, which hindered efforts to establish trust. Moreover, political parties like the SNLD and SNDP have distinct ideologies and goals. While the SNDP collaborated with the election commission established by the military, the SNLD opposed it. This demonstrates a multitude of political positions in Shan State. Consequently, will the claim of autonomy by the non-CSSU member Mong La group have an effect on efforts to achieve Shan unity?

The NDAA has not been included in the CSSU’s efforts toward Shan unity. One key reason for this exclusion lies in the group’s distinct identity. Unlike the RCSS/SSA and the SSPP/SSA, the NDAA has not identified itself as a Shan State Army. Why? In order to answer this question, it is important to discuss their historical background and aspirations:

RCSS/SSA:

In January 1996, the Mong Tai Army, commanded by Khun Sa, surrendered bloodlessly to the Myanmar Army. Several thousand of his soldiers surrendered an arsenal of weapons. Nonetheless, remnants of the Shan United Revolutionary Army (SURA), formerly known as the MTA and commanded by Yord Serk, established the RCSS/SSA. As it gradually reformed and conscripted, it was renamed the Shan State Army-South to differentiate it from the actual Shan State Army (SSA), which was established in 1964. In May of 2000, the RCSS was founded as a political front for the SSA-South. Its headquarters are located in Loi Tai Leng, Mong Pan Township, Shan State, with between 7,000 and 10,000 members. It is primarily active in southern Shan State, although it is also prevalent in other regions of Shan State. In 2015, the RCSS/SSA, along with other ethnic armed groups, ratified the nationwide armistice agreement (NCA) with the Thein Sein government, whereas the SSPP/SSA refused to sign the NCA.

SSPP/SSA:

The Shan State Progress Party/Shan State Army was established on April 24, 1964. After negotiations with the military’s State Peace and Development Council (SPDC), the SSPP signed a ceasefire in 1989 and was able to secure a degree of autonomy for the territories under its control, establishing Special Region 3 of the Shan State with its headquarters in Wan Hai in Kehsi Township. Nam Kham, Langkho, Hsipaw, Kyauk Mae, Mong Hsu, Tang Yang, Mongyai, Kehsi, and Lashio Township were among the areas it controlled. It consists of approximately 4,000 combatants. Even after signing a cease-fire, the Myanmar military continued to launch attacks against the SSPP/SSA. The SSPP/SSA, along with other EAOs that did not sign the NCA, established the Federal Political Negotiation and Consultative Committee (FPNCC), which was commanded by the United Wa State Army (UWSA), the most potent ethnic armed group with between 20,000 and 30,000 personnel.

NDAA: why not SSA-East?

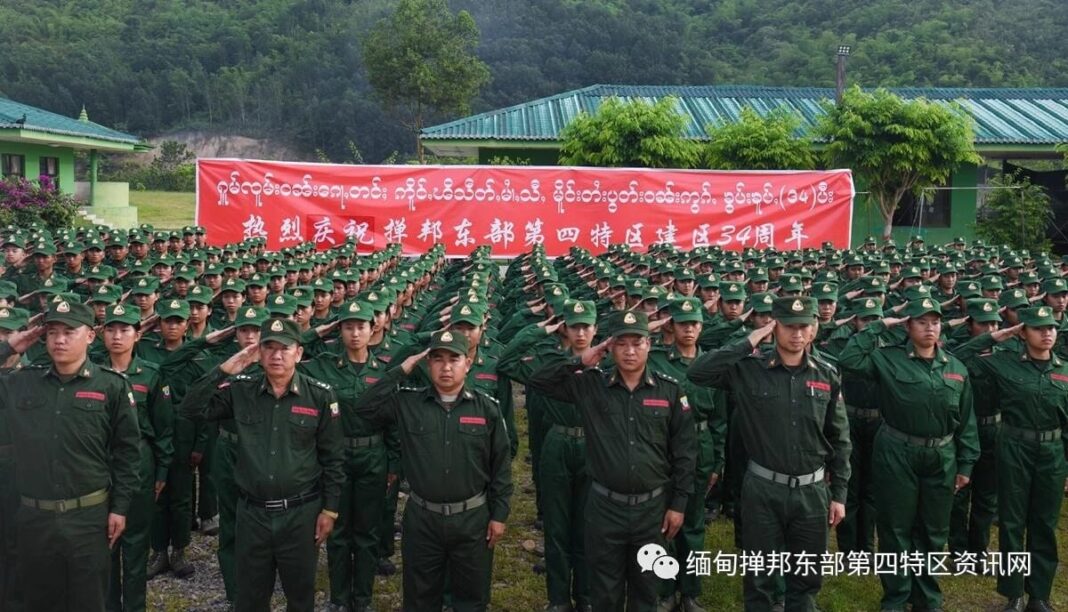

Due to the collapse of the Communist Party of Burma (CPB), the NDAA signed a ceasefire with the Myanmar military regime in 1989, becoming one of the first factions to make the ceasefire agreement. The NDAA controls Mong La, Nanban, and Sele districts, which constitute Special Region 4 of eastern Shan State. It covers 4,952 square miles, and most of the areas are mountainous. The population is around 100,000. Other communities account for only a few hundred to a few thousand individuals. There are a total of 413 communities. This Special Region 4 has no representatives of Myanmar authorities, including Myanmar military, police, and bureaucratic officials. After thirty years of ceasefire agreement, the NDAA is now a flourishing, peaceful border community.

The NDAA, like SSPP/SSA, has not signed the NCA and is a member of the FPNCC. The RCCS/SSA is not a member, however.

It can be argued that the NDAA’s claim to autonomy in Special Region 4 is motivated by socioeconomic concerns and a desire for autonomy. Nonetheless, the pursuit of autonomy, despite its significance for local development and governance, could be viewed as a deviation from the collective effort to achieve Shan unity.

In order to achieve genuine Shan unity, it is necessary to recognize the various perspectives and aspirations of all Shan communities. Building a cohesive Shan identity and a unified vision for the future requires a collaborative strategy that embraces diversity while working towards shared objectives. What then?

Leave a Comments