“How much is a carton of eggs and a packet of instant noodles?”, in a low voice, Zaw Aung asked the shopkeeper.

Zaw Aung, from Myanmar, works as a migrant worker in Chiang Mai, Thailand, also known as Zinme amongst those from Myanmar. People like him, who are migrant laborers, must be cautious with their spending, including food expenses.

Thailand, right next door to Myanmar, has been a popular choice for people from Myanmar seeking better job opportunities and higher pay compared to what’s available in Myanmar. The ongoing long civil war in Myanmar has made life increasingly tough, pushing many to leave their homes. The 2021 Coup added to the challenges, causing a significant increase in the number of people seeking work opportunities in Thailand.

Some people who work abroad obtain employment through formal Memorandum of Understanding (MOU), while many others go through informal routes. People like Zaw Aung, who enter other countries (Thailand for example) without proper documentation to seek job opportunities, often encounter significant challenges.

“I couldn’t find a job immediately after arriving in Thailand,” Zaw Aung shared with a somber expression. “It was tough for me since I lacked legal documents. Employers typically prefer workers with some form of legal document. As a result, I remained unemployed for about a month when I first arrived,” he added, with a sense of sadness.

When considering work in Thailand, it’s important to understand what employers want. They mostly prefer workers who have the proper identification. This is tough for people who come to the country illegally. Therefore, even though they came in without permission, they need to find a way to get legal identification.

“I had to obtain some form of legal paperwork through the same agent who brought me to Thailand. I came to Thailand with borrowed money, and inflation was rising back in my home country. Consequently, the interest on the money I owed increased. On top of that, I didn’t find a job quickly upon arriving. It’s been really tough. So, I need to be extremely cautious with the money I have. This is why I mostly eat eggs and instant noodles; it’s a way to cut down on expenses for the month,” Zaw Aung shared, his tone reflecting his difficulties and a sense of disappointment.

To address the economic repercussions of the COVID-19 pandemic, the Thai government made an announcement on July 5, 2022. They declared that migrant workers from Myanmar, Laos, Cambodia, and Vietnam, who lacked proper legal documentation in Thailand, would be granted a temporary residence and work permit known as a “pink card.” This pink card allows them to engage in employment within designated areas.

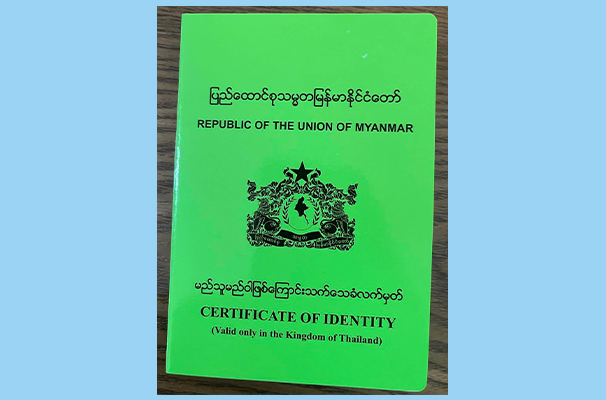

The process of obtaining the necessary legal documents starts with obtaining a work permit smart card. After this, the next step involves applying for a residence permit, which replaces the need for a passport for individuals without one. Instead of a passport, they are issued a Certificate of Identity (CI) by the authorities.

If, for various reasons, someone is unable to obtain the CI, the last resort is to obtain a Non-Thai Identification Card, commonly known as a Pink Card. Typically, the cost of obtaining a Pink Card through agents ranges between 7,000 to 15,000 Baht. It’s important to note that the card must be renewed by February 13, 2021, to remain valid.

A further expense is the cost of renewing the identification card for another year, extending its validity until the end of 2024. The starting fee for extending the Certification of Identity (CI) is approximately 9,000 Baht. However, the overall expenditure may increase to 15,000 Baht if an individual also needs the Myanmar Government’s Oversea Worker Identification Card (OWIC).

“We have to pay whatever price brokers want because we are dependent on them. Getting these identification cards becomes a necessity, as it is incredibly challenging to find a job without them, which directly affects our livelihoods. With families waiting for our support back in Myanmar, there’s an urgency to send money home,” shared Zaw Aung, bringing up the hefty cost of identification cards, a burden he views as expensive and undesired.

“As soon as I paid for the permit document and covered my living and food expenses from my salary, there was barely enough left to start repaying my debt. I feel heavy every time I talk to my family back home because I can’t send them money yet. It took me six months to pay off the cost of the identification card. So, I had to be extremely cautious with my spending, especially considering the interest on the borrowed money,” Zaw Aung shared, his face reflecting the difficult journey he endured in pursuit of these crucial identification cards.

Typically, migrant employees are supposed to rely on their employers to help them obtain identification cards. Employers are essentially accountable for helping or supporting their employees during this process. However, in practice, many employers lack a thorough understanding of this process or are frequently too busy to get involved.

Even when employers are involved in the process, they may fall short in providing all the necessary documents to the employees. The employees may later face difficulties as a result, especially if they want to change jobs.

“I had an experience where my former employer, the boss I used to work for, helped us get work permits, but unfortunately, they didn’t provide all the required documents,” recalled a young migrant worker who moved from Bangkok to Chiang Mai for employment. “We had to cover the expenses, but when we decided to change our workplace, they didn’t return our pink cards. This is why we now find ourselves having to apply for new identification cards all over again,” the worker explained, highlighting the challenges faced by migrants when employers don’t fulfill their responsibilities regarding these documents.

Migrant workers often face language barriers when dealing with government offices, making it difficult for them to handle the process themselves. As a result, they must rely on various agencies and brokers to assist them in obtaining identification cards or work permits.

Sai Thiha, working in Bangkok, explained the situation, saying, “When we need to get a pink card, we have to go through brokers and agents because we can’t speak Thai, and we don’t understand the process to apply on our own. We don’t even know the office hours, so we have to go through brokers to obtain these identification cards. When agents inform us about the opening for identification card issuance, we then proceed to apply.”

However, relying on brokers and agencies is not without difficulties. While some agencies operate fairly and responsibly, managing the entire document acquisition process, there are others who charge excessive fees compared to other agencies.

Even though some migrant workers possess legal work permits, they may not be well-informed about all the necessary details, information, and procedures. Consequently, some workers with valid permits might inadvertently allow them to expire because they are unaware of when and where to renew. This situation results in many migrant workers having expired or invalid permits or even overstaying their permits.

In light of these issues, the Migrant Workers’ Information Center in Chiang Mai, Northern Thailand, plays a crucial role by regularly disseminating announcements from the Thai government or local authorities that are relevant to migrant workers. These notices are translated into a number of migrant workers’ accessible languages.

Therefore, to ensure the maintenance of their work permits and legal status while working in Thailand, individuals must actively stay informed and keep a close eye on this information.

Leave a Comments