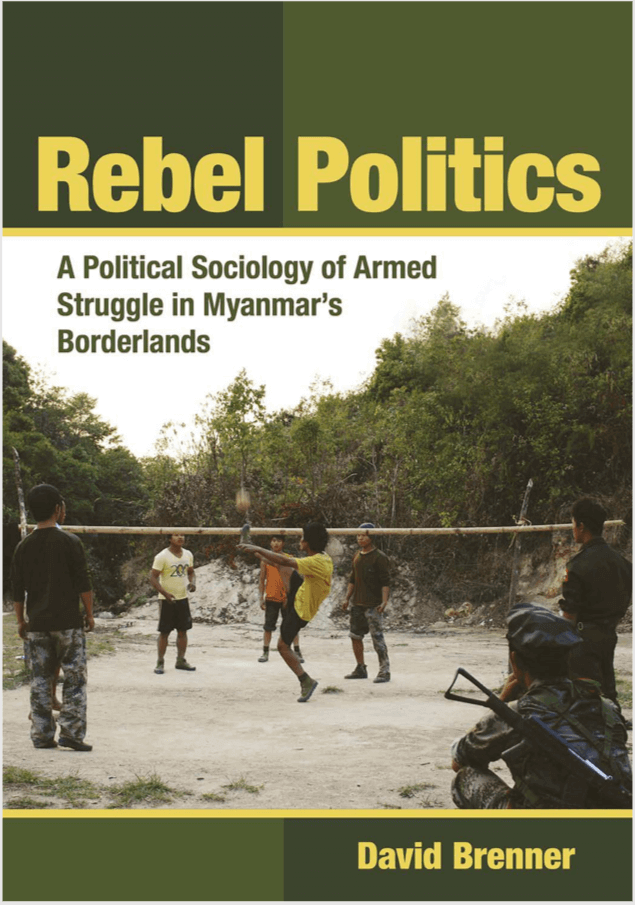

A new book came out in October 2019, titled “Rebel Politics – A Political Sociology of Armed Struggle in Myanmar’s Borderlands,” written by David Brenner, a lecturer in International Relations at Goldsmiths, University of London.

By David Brenner

The book is a comparative study zeroing in on the Kachin Independence Organization/Army (KIO/KIA) and the Karen National Union/ Karen National Liberation Army (KNU/KNLA), which is peppered with numerous interviews involving local actors and grassroots within the rebel territories by the author, making it very readable and shedding lights on hitherto unknown perspectives covering a wide range opinion that have never been made public before.

The 162-page book which has five chapters includes: theoretical underpinning; historical background of Kachin and Karen rebellion; KNU internal power rivalry; KIO change of guard which was taken over by new generation rebel officers; and the conclusion, drawing from four-track assumption, which determines the political course of the rebel armies.

The theoretical underpinning is that in what the author called the “dynamics of internal contestation” determines the collective conflict and also shapes the negotiation strategies of the rebel organizations.

He writes: “(It) identifies reciprocal exchange relations, social identification, and the struggle for recognition as the core drivers of the building and erosion of leadership authority within rebel movements.” In other words, the outcome of power contest shapes the collective political course and negotiation strategies.

The following three chapters described historical background of Kachin and Karen rebellion, including the internal power competition within the rebel organizations and the outcome results, which reflect the grassroots aspirations conducted by leadership that have managed to be in the driver’s seat.

For example, he explained that the KIO recent confrontation policy is due to the power takeover of new generation with the endorsement of the grassroots, while the KNU rapprochement policy is because of the General Mutu Say Poe and Padoh Saw Kwe Htoo Win faction, whose base are central and southern brigades and favored co-optation. The rival or opposition faction headed by Naw Zippora Sein and Baw Kyaw Heh of northern brigades lost their political clout following the lost of election in the last 16th KNU Congress, in 2017, have been skeptical of the nationwide ceasefire agreement (NCA)-based peace process and thus considered as being hard-liners.

The revival of KIO as a fighting force in 2011, after the breakdown of 17 years ceasefire, was due to the Kachin grassroots dissatisfaction with the leadership, who became rich and corrupted since mid-2000s because of the given economic incentive by the state power through rapprochement, turning back into an effective resistance outfit which many have written off as weak and lack of fighting capability. This is because the senior KIO leadership alienated the young officers who in turn remobilized the grass roots, including the rank-and-file of the military and took over the reign.

“While the two movements proceeded through different stages at different times, they essentially followed a similar trajectory along four tracks: leadership co-optation; group fragmentation; contention over authority; and renewed resistance from within,” writes the author.

The linkage is explained as partial leadership co-optation creates horizontal conflict, meaning: rift between the privilege leadership profiting from economic incentive kickbacks and the under-privileged young officers; and vertical conflict between the grassroots and the rebel leadership, due to latter’s inability and lack of political will to advance the Kachin people’s aspirations. This in turn, push for group fragmentation and contention over the authority, at the same time. And all these paved the way for renewed resistance from within. KIO’s young officers coup displacing the old clique is the case in point.

Thus, the author main thrust along the said four tracks could be taken as a valid sequence of argument. Moreover, his soliciting that the rebel organization should be given more attention and aspirations of the grassroots, including above all the struggle to have their identities recognized.

While the book is informative, full of hitherto unpublished facts and plausible advocation on behalf of the ethnic armed organizations (EAOs) in general, there is also a negligence of reality, perhaps unintentionally, where the description of NCA-Signatory-EAOs is concerned.

Take for example the paragraph which writes: “The KNU is the only sizable rebel group that signed the NCA in 2015. Most other signatories are counterinsurgency militias for the military or have no substantial armed wings. At the time of writing, the most powerful ethnic rebel armies remain on the battlefield.”

The author failed to mention that at least another strong signatory-EAO, the Restoration Council of Shan State (RCSS) with some 8000 to 10,000 according to the conservative estimation is a formidable rebel army, comparable to the KNU.

Other than that, it is an excellent book soliciting a trend which scholars should take heed in developing a better understanding of rebellion and its social foundations.

In conclusion he pointed out that the major reason for the continuation of armed conflict is because the government cannot control and rein in the Tatmadaw.

He further writes: “As Tatmadaw generals have long profited from perpetuating conflict, it was naïve to think they would simply give up their sources of power and wealth.”

He pointed out that a genuine willingness by all sides to make peace is essential if the conflict is to be resolved. The author’s closing line writes: “An important first step in that direction, as this book advocates, is to listen to rebels themselves.”

But the book hasn’t gone far enough to suggest the legitimization of the rebel-rulers like Ashely South & Christopher M. Joll, in their piece titled: “From Rebels to Rulers: The Challenges of Transition for Non-state Armed Groups in Mindanao and Myanmar,” published on 07 Apr 2016, pointed out.

It writes: “Much will depend on whether, and to what extent, the Myanmar government and international actors (including but not limited to bilateral aid donors) are willing to recognize the legitimacy of EAGs (ethnic armed groups).”

For the time being, it seems the EAOs will have to be prepared for a long wait for such rendering of legitimization to become a reality.

Leave a Comments