by

Martin

Over the past seven years, ethnic health organizations (EHOs) and community-based health organizations (CBHOs), which have provide health services to ethnic populations in the ceasefire, active conflict, and internally displaced areas of Myanmar, have engaged in discussions with Myanmar government officials to explore potential opportunities for technical exchange, shared training, and increased cooperation around health services. These EHOs/CBHOs view such opportunities for coordination and cooperation as critical to improving the lives of the ethnic people in Myanmar. The concept of expanding and enhancing health services through increased coordination, cooperation, and long-term alignment between the EHOs/CBHOs and Myanmar government toward a new devolved health system has been broadly defined as “health convergence”. This concept of health convergence has garnering much attention over the past few years as Myanmar moves toward “political convergence” and sustainable peace.

Political Context

Health is not political. However, health convergence is political because:

- EHOs and CBHOs operate in ethnic armed organization (EAO) – controlled areas.

- EHO parent EAOs are engaged in peace negotiations for “political convergence”.

- Health convergence progress is dependent upon political convergence progress.

- A new devolved health system requires changes to Schedules 2 and 5 of the 2008 Constitution.

- The health system, being implemented by the National League for Democracy (NLD) government through its National Health Plan (NHP), is a deconcentrated-delegated health model, not a devolved health model of the EHOs/CBHOs and aligned with the democratic federal union desired by the ethnic people.

Because health convergence is political, international actors – foreign governments, international development agencies, and international nongovernment organizations (INGOs) – must understand the political environment. The new civilian Myanmar government, elected in 2010, saw the ethnic conflicts as hampering the transition to a democratic country finally at peace with itself. Thus, it initiated peace negotiations with the EAOs, resulting in a series of bilateral ceasefire agreements to begin a process of national reconciliation. These peace negotiations made some progress toward a multi-lateral and broader Nationwide Ceasefire Agreement (NCA) which was initially signed by eight EAOs in October 2015 and later by two further EAOs.

The peace negotiations have continued with the new NLD government of Aung San Suu Kyi. This government has convened a series of 21st Century Panglong Conferences in furtherance of peace negotiations and confidence building. The State Counselor, Aung San Suu Kyi, stated that these Conferences are one of the steps for a democratic federal union as noted in the Myanmar government’s Seven Step Roadmap:

- Review the political dialogue framework.

- Amend the political dialogue framework.

- Convene Union Peace Conferences — 21st Century Panglong Conferences – in accordance with the amended political dialogue framework.

- Sign a Union Accord based upon the results of the 21st Century Panglong Conferences.

- Amend the Union Constitution in accordance with the Union Accord and approve the amended Union Constitution in the Union Parliament.

- Hold multi-party democratic general elections in accordance with the approved Union Constitution.

- Establish a democratic federal union in accordance with the results of multi-party democratic general elections.

Presently, the peace process continues to be stalled in the Step Three of the Seven Step Roadmap since the Tatmadaw (Burma military) refuses to discuss any issue which is in conflict with the 2008 Constitution. Thus, no meaningful political dialogue has occurred toward the self-autonomy, resource sharing, and ethnic equity promised seventy years ago during the establishment of the independent country and demanded by the ethnic people. Furthermore, the Tatmadaw continues to use force to bring about a military solution to the ethnic conflicts.

Unfortunately, many international actors have made a faulty conclusion that the ethnic areas are in a post-conflict period. They are confusing the democratic election of the NLD government along with the ceasefire agreements and peace conferences as the beginning of a post-conflict era in Myanmar. Hence, they view everything from this perspective, including “time”. In a post-conflict period, the “time” is “now”. Thus, these international actors want the convergence of the ethnic and Myanmar government health systems to happen “now”, and have directed funding and programs with this post-conflict “now” in mind.

It is post-conflict, but only in the Bamar–dominated areas of Central Myanmar:

- Ayeyarwady Region

- Magway Region

- Mandalay Region

- Naypyitaw Union Territory

- Yangon Region

But the ethnic people and EAOs in Kayah, Kayin, and Mon States; and Sagaing, Bago, and Tanintharyi Regions know otherwise:

- Low-moderate intensity conflict period

- No sustainable peace: only ceasefire agreements

- Buildup of Tatmadaw capabilities – camps, forces, and armaments

- Large numbers of internally displaced persons (IDPs) remain hiding in the jungle

The people and EAOs in Rakhine, Chin, Kachin, and Shan States really know otherwise:

- High intensity conflict period with continuous Tatmadaw offensive operations utilizing fighter aircraft, attack helicopters, and artillery

- No, or broken, ceasefire agreements

- Increasing numbers of fleeing IDPs as well as civilian deaths and injuries due to the fighting

The conclusion of the ethnic people and EHO/CBHOs is that the present “time” is a low-high intensity conflict period. Furthermore, health convergence will coincide with the peace negotiations and probably occur three-five years in the future. The post-conflict period will begin with the establishment of a democratic federal union (i.e., Step Seven of the Seven Step Roadmap) and the implementation of security sector reform of the Tatmadaw. This is the EHOs’/CBHOs’ perspective upon which their planning, budgeting, and operations are based. Since the EHOs/CBHOs and international actors come from two different perspectives with two different related timelines, they have been talking pass one another and not to one another.

Until there is sustainable peace in a true post-conflict period, health services will be provided to an ethnic population in areas administered by the EAOs through the EHOs/CBHOs. The EAOs control this territory and its population, and will deny access to it by the Myanmar government health staff until there is sustainable peace. Consequently, the EHOs/CBHOs will require continued funding and technical assistance from international actors to provide health services to its served ethnic population until there is sustainable peace which ushers in a real post-conflict period. Only then, can health convergence begin to occur.

Ethnic Health System

The extensive ethnic health system of the EHOs/CBHOs was initially established under the authority of the EAOs to meet the health needs of ethnic people in the conflict-affected areas controlled by them. The health services provided by the EHOs/CBHOs are based upon a comprehensive primary healthcare model with health services delivered through a mix of both mobile outreach and community clinics.

Since their beginnings, the EHOs/CBHOs have found ways to work together, recognizing the importance of developing common health policies, standards and protocols, and standardizing their health information systems and health worker training curricula. Together, these EHOs/CBHOs have built a sustainable community-level primary healthcare system which provides health services in ceasefire, active conflict, and internal displacement areas to the ethnic people inside Myanmar and migrants/refugees in the Myanmar-Thailand border areas:

- 725,000 served population

- 10 of 14 states/regions of Myanmar

- Thai border provinces

- 4,400 health workers (Myanmar)

- Types of health workers:

- Health Assistants

- Medics

- Reproductive/Maternal & Child Health Workers

- Community/Village Health Workers/Volunteers

- Laboratory Technicians

- Pharmacy Technicians

- Traditional Birth Attendants

- 247 mobile health teams & fixed health clinics (Myanmar)

- Curative, preventative, promotive, rehabilitative, palliative, and mental health services

Source: Health Information System Working Group (2018)

The key ethnic organizations supporting this ethnic health system are the Health Convergence Core Group (HCCG), Health Information System Working Group (HISWG), and Ethnic Health System Strengthening Group (EHSSG). The HCCG was established by a group of EHOs/CBHOs to lead the convergence initiatives of the EHOs/CBHOs and is supported in this effort by the HISWG and EHSSG. The EHOs/CBHOs also formed the HISWG to collect key health data from the partner EHOs/CBHOs, conduct analysis, and publish reports about the ethnic health system for planning, decision making, and advocacy. The EHSSG was also established by a group of EHOs/CBHOs to enhance the key building blocks of the ethnic health system as set out in the World Health Organisation’s Health System Framework:

- Leadership and governance

- Health information system

- Health workforce

- Health financing

- Access to essential medicine, medical supplies, and medical technology

- Service delivery

Devolved Health System

The HCCG commissioned a health system policy options’ paper entitled A Federal, Devolved Health System for Burma. This Paper outlines policy considerations for the decentralization of health services in Myanmar. Among these considerations were various structures for the decentralization of political, administrative, and fiscal health powers:

- Deconcentration – Transfer of selective health administrative authority and responsibilities from the Union Ministry of Health and Sports (MoHS) to its sub-Union offices at state/region, district, division/zones/territory, township, and lower levels of government.

- Delegation – Transfer of selective health administrative authority and responsibilities from the MoHS to organizations not directly under the control of the Ministry, such as autonomous state/region and/or sub-state/region government agencies, EHOs/CBHOs, INGOs, local nongovernment organizations, and private health service providers.

- Devolution – Sharing of selective political, administrative, and fiscal health authority and responsibilities between the MoHS and autonomous state/region and sub-state/region levels of government through constitutional provisions and statutory laws/regulations.

In this context, the HCCG considered various global health system models and noted the following distinctions:

- Deconcentrated-delegated health systems: The government is responsible for the health care of the country’s population – curative, preventative, promotive, rehabilitative, palliative, and mental health services.

- Devolved health systems: The government and the people are both responsible, to varying degrees depending on structure, for the health care of the country’s population – curative, preventative, promotive, rehabilitative, palliative, and mental health services.

The Policy Options’ Paper concluded that a devolved health system is the most compatible with the situation in Myanmar as it is more community-based, more responsive, and more aligned with the political aspirations of the ethnic people for a democratic federal union. Also, devolved health systems appear to be a generally-accepted global model.

Within a devolved health system, political, administrative, and fiscal health powers would be shared between the Union and sub-Union governments:

Political – The sharing of political authority and responsibilities by the MoHS with state/region governments to allow state/region parliaments to have specific legislative authority over their health sector. Key political power sharing of authority and responsibilities between the Union and sub-Union governments in a devolved health system are to:

- Establish the vision, mission, goals, and policies for the health sector;

- Effectively allocate financial, human, material, infrastructure, technological, and other resources toward plans and programs to achieve health sector goals and carry out missions; and,

- Oversee the health sector.

Administrative – The sharing of administrative authority and responsibilities by the MoHS with state/region and lower levels of government for the management of the state/region health sector. Key administrative power sharing of authority and responsibilities between the Union and sub-Union governments in a devolved health system are to:

- Convert the health sector vision into reality – outcomes and impact; and,

- Efficiently manage the allocated resources to carry out plans and programs to achieve health sector goals/timelines within policy guidelines.

Fiscal – The sharing of fiscal authority and responsibilities by the MoHS with state/region governments for the financing of health care through taxation, international grants/loans, and transfers/equalization payments from the Union government, and the allocation of funds within the state/region health sector. Key fiscal power sharing of authority and responsibilities between the Union and sub-Union governments in a devolved health system are to:

- Formulate a realistic budget to achieve health sector goals;

- Collect and disburse funds to the health sector in accordance with the budget and policy guidelines; and,

- Monitor the health budget.

Such a devolved health system authority-responsibility sharing arrangement is very much aligned with the ethnic peoples’ political desire to establish a democratic federal union with the sharing of political, administrative, fiscal, economic, resource, territorial, and security powers. However, devolution is a highly-sensitive political issue, and must be considered and implemented as a component of overall political reform.

Over the past seven years, the EHOs/CBHOs have made determined efforts to build dialogue and cooperation with health officials at various levels of the Myanmar government, and develop models of what a devolved health system could look like in a democratic federal union. The Policy Options’ Paper presents an example power sharing matrix reflecting the allocation of health authority and responsibilities among the Union, state/region, and township levels of government within a devolved health system in a democratic federal union:

Devolved Health System in a Democratic Federal Union

| Level of Government | |||

| Health System Authority & Responsibilities | Union | State/Region | Township |

| Setting norms, standards, & regulations | X | ||

| Policy formulation | X | X | |

| Revenue generation/resource allocation | X | X | |

| Data collection, processing, & analysis | X | X | X |

| Program/project design | X | ||

| Monitoring/oversight of hospital/health facilities | X | ||

| Facilities & infrastructures | X | ||

| Salaries & benefits | X | ||

| Contracting hospitals | X | ||

| Budgeting/expenditure authority | X | X | |

| Purchasing/warehousing drugs/supplies | X | X | |

| Hospitals & health facilities management | X | X | |

| Training & staffing (planning, hiring, & firing) | X | X | |

Source: A Federal, Devolved Health System for Burma

Unfortunately under the 2008 Constitution, health is a political, administrative, and fiscal power reserved solely to the Union government. Moreover, the current NLD government is implementing a deconcentrated-delegated health system model for its NHP which is based upon these centralized health powers. In this context, the Union government has exclusive legislative power over health policymaking, with state/region governments having only a coordination role. The health programs in the state/region health departments would remain operated by Union-level staff and be expected to continue to result in inefficiencies, delays, and programs not suited to local community needs and priorities.

Health Convergence

In concert with the ongoing ceasefire agreements and peace negotiations between the Myanmar government and EAOs, the EHO/CBHOs have been working together to converge their extensive community-based health system with the Myanmar government’s health system. The aim is to offer better health service, access more of the ethnic population, improve health systems and policies, and gain Myanmar government recognition and accreditation of the EHOs/CBHOs and their health workers. This health convergence is viewed from an ethnic perspective as:

The systematic, but separate, long-term alignment of the Myanmar government and EHO/CBHO health programs/services, coverage, policies, systems, and structures toward a common vision and goals until a democratic federal union has been firmly established with a devolved health system.

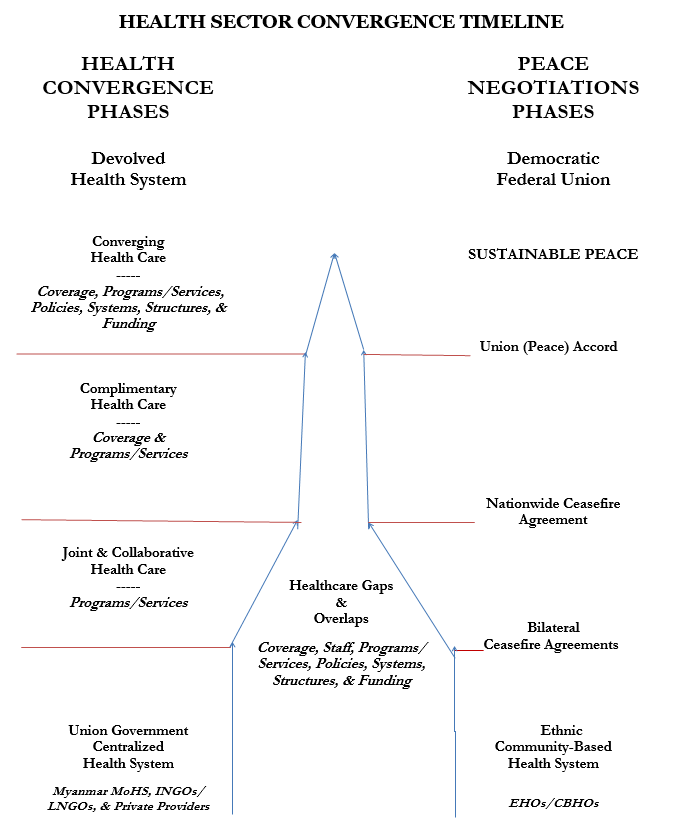

Furthermore, health convergence has been seen to have three distinct phases:

First Phase: Convergence of the CBHOs.

Second Phase: Convergence of the EHOs with CBHOs into an ethnic health system.

Third/Final Phase: Convergence of the ethnic health system with the Myanmar government health system into a new devolved health system in a democratic federal union

The following diagram (so-named the “Rocketship”) attempts to depict a parallel process whereas the timing and direction of health convergence is dependent upon the timing and direction of the peace negotiations between the Myanmar government, Tatmadaw, and EAOs. The diagram’s slopes reflect positive changes in the direction of health convergence which are dependent upon similar positive changes in the peace negotiations. A key component of any positive movement toward health convergence is that the slope of the Myanmar government health system shifts toward the mutually converging slope of the ethnic health system with an appropriate devolution of political decision-making, administrative, and fiscal authority and responsibilities in a new devolved health system of a democratic federal union. Health convergence can only be successful if it is mutual.

However, the Myanmar government considers the EHOs/CBHOs as either integrated into the deconcentrated health system of the Myanmar government or a separate health service provider with delegated services provision responsibilities. The EHOs/CBHOs object to the use of the word “integration” when discussing health convergence since it implies that the EHOs/CBHOs are to be absorbed within the Myanmar government health system with all key political, administrative, and fiscal health powers still centrally exercised by the Union government.

The EHOs/CBHOs do not see health convergence as them “joining” the existing Myanmar government health system in any shape or manner. In essence, this would mean that the EHOs/CBHOs would essentially Disarm by “surrendering” their international actor funding to a Myanmar government-controlled purchaser pool, Demobilize by “dissolving” their leadership structures and organizations, and Reintegrate through their “return to the legal fold” of the MoHS. “Joining” the centralized Myanmar government health system would thus be considered to be “DDR” of the EHOs/CBHOs with them having only service delivery responsibilities and no decision-making, administrative, or fiscal authority. The EHOs/CBHOs want true health sector reform with the existing Myanmar government and ethnic health systems converging into a new devolved health system of a democratic federal union.

.

Universal Health Coverage

The Myanmar government, through its NHP, and EHOs/CBHOs share the same goal of Universal Health Coverage (UHC). However, each party had a different perspective about the appropriate approach to this goal.

The Myanmar government’s NHP views UHC as being implemented through a deconcentrated-delegated health system with all key political, administrative, and fiscal health authority centralized at the Union level as it is now. This NHP view is not consistent with a true reform of the health sector toward a democratic federal union. In contrast, the EHOs/CBHOs maintain their perspective that political decision making, administrative control, pool funding (taxes, Union government transfer/equalization payments, and grants/loans from international actors), and pool funding allocation/management (purchasing) for UHC and the health sector in general must be at or shared with the state/region governments.

Thus, the EHOs/CBHOs do agree with the UHC concept, a basic essential package of health services, importance of data sharing to inform health planning, and the inability of the Myanmar government to implement UHC by itself, especially in the ethnic service areas. However, the EHOs/CBHOs do not agree that all key political decision making, administrative control, and pool funding/purchasing for UHC and the health sector should be centralized at the Union government level.

The convergence point of these two perspectives is amendments to the 2008 Constitution which add health powers to Schedule 2 (Region/State Legislative List) and expanded taxation authority in Schedule 5 (Taxes Collected by Regions/States) to share political, administrative, and fiscal health authority and responsibilities between the Union and states/regions in respect to a devolved health system. Such a constitutional amendment can be accomplished through either a NHP-inspired parliamentary action or Union Accord (i.e., peace agreement). Unfortunately, the NLD government, in its NHP, has failed to consider parliamentary Schedules 2 and 5 amendments to the 2008 Constitution for any sharing of political, administrative, and fiscal health powers between the Union and sub-Union levels of government in a devolved health system.

Key Health Convergence Issues

Among the challenges facing the EHOs/CBHOs working inside Myanmar are the issues of recognition, registration, and accreditation. Despite increased dialogue with the Myanmar government, the Myanmar government still does not officially recognize the EHOs/CBHOs, with most all remaining unregistered. Moreover, the Unlawful Associations Act of 1908 remains in effect and stipulates imprisonment for those meeting with or aiding unregistered organizations. Such issues remain impediments to more wide-ranging, official collaboration between the Myanmar government and EHOs/CBHOs.

The lack of registration further restricts funding opportunities for many EHOs/CBHOs. However, registration would force the EHOs/CBHOs to provide key information to the Myanmar government. EHOs/CBHOs fear this information could be used to control them, monitor their activities in EAO-controlled areas, and otherwise pose threats to their staff and served ethnic populations prior to the establishment of sustainable peace in the country.

A related issue is health worker recognition and accreditation which is central to the ability of the EHOs/CBHOs to work effectively in their ethnic areas. For decades, the EHOs/CBHOs have developed their own standardized curricula for different health staff positions. Yet, their health workers are not officially accredited, leaving them under the constant threat of arrest and vulnerable to intimidation in their work by Myanmar government officials and Tatmadaw soldiers. Accreditation is seen as an important step in ensuring that the EHO/CBHO health staff is protected from arrest, and recognized as an integral part of the health system in Myanmar and equals to comparably qualified Myanmar government health workers. Addressing issues of health worker recognition and accreditation is seen as an early, essential step towards health convergence and achieving a joint approach toward addressing health service inadequacies and the shortages of qualified health workers in the ethnic areas.

Historically, international actors have funded the EHOs/CBHOs to support the provision of health services to local ethnic communities which have little or no access to basic health services due to ongoing fighting or internal displacement. However since Myanmar’s 2010 elections, a number of major international actors have withdrawn their financial support from the EHOs/CBHOs, preferring to work with the Myanmar government and fund health programs that are implemented with government approval. With the great optimism in the new NLD government, the risk of losing funding for ethnic health services has only increased. As a result, the EHOs/CBHOs have been faced with a worsening funding situation. Although some international actors continue to support the EHOs/CBHOs, there is the real fear that the EHOs/CBHOs will become more sidelined as health service providers in their ethnic communities because of the lack of funding for existing health services. Adding to this marginalization fear is the Myanmar government’s strengthening its hold on both national and international resources directed toward the health sector, and pushing forward its deconcentrated-delegated model of health service provision with the technical and financial assistance of international actors.

Furthermore, the health services expansion, pursued by the MoHS with the backing of international actors, appears to be moving ahead in the ethnic areas with little opportunity for input from those in the community or the EHOs/CBHOs. This has resulted in service overlaps and gaps, vertical health programs which clash with the strong community-managed primary healthcare approach that has been developed over the past decades by the EHOs/CBHOs based upon local community needs and priorities, and local human resources being poached by international actors that offer higher salaries. There is also a fear among the ethnic people that some health programs, supported by international actors, may have been guided towards specific ethnic areas by the Myanmar government as a component of a counter-insurgency “cut” strategy to separate the EAOs from their supporting ethnic populations.

Summary

With more than thirty years’ experience and trust built with ethnic communities inside Myanmar, the EHOs/CBHOs are best placed to take the leadership role to provide health services to their served population. However, concrete solutions must be found for the skilled human resources and capabilities of the EHOs/CBHOs to be recognized and provided with the authority necessary to operate legally in ethnic areas, instead of simply being “integrated” into the Myanmar government’s deconcentrated-delegated health system.

The delivery of health services can play an important role in peace building. Yet, there are concerns in the ethnic areas that moving too quickly on health convergence, without progress in the peace negotiations, may be detrimental to long-term ethnic reconciliation. While supporting these peace negotiations, the movement and timing of health convergence entails certain real risks to ethnic health workers and their served population should the peace negotiations breakdown and fighting resumes, expands, or intensifies. Consequently, health convergence must not put EHO/CBHO health workers, their served population, or peace negotiations at risk.

International actors can greatly enhance the health convergence activities of the EHOs/CBHOs through:

- Increasing their awareness of the ongoing sensitive political and conflict situations in the ethnic areas, even in light of recent political reforms.

- Exploring funding and technical assistance opportunities and health initiatives that support both health convergence and the peace process.

- Ensuring that health services are delivered in alignment with ethnic peoples’ needs, priorities, and in a way that supports and “does no harm” to the peace process.

- Recognizing the EHOs/CBHOs and their knowledge, experience, skill sets, health workers, and population coverage built up over past thirty years and supporting them as the health service providers in their ethnic communities.

- Promoting and directly supporting ethnic community-based health programs through financial support, capacity building, technical assistance, medicine, and medical supplies.

- Encouraging the participation of EHOs/CBHOs in seminars, meetings, workshops, and related activities in respect to health services and health sector reform.

International actors have spent tens of millions of dollars over the past three decades helping to build a devolved community-based, bottom-up, ethnic health system. They should not solely support, implicitly or explicitly, a top-down deconcentrated-delegated health system of the Myanmar government which seeks to “DDR” the ethnic health system. Moreover, international actors should do an objective Do No Harm Analysis which considers the:

- Obstruction of health power sharing negotiations by intentionally favoring only the Myanmar government health system through funding and technical assistance decisions.

- Refusal to fund the health services of the EHOs/CBHOs to their served populations in EAO-controlled areas.

- Implementation or funding of health initiatives directed by the Myanmar government to either undermine or weaken the holistic relationship between the EAOs and their ethnic population or reward those EAOs which have signed or will sign the NCA.

In summary, the key points to understand from an ethnic perspective are:

- Health convergence is political, associated with the peace process, and will take many years.

- The ethnic areas are not in a post-conflict period, but in a low-high intensity conflict period.

- The ethnic health system is vast.

- The ethnic people want a devolved health system in a democratic federal union.

- UHC is the goal of the EHOs/CBHOs through their ethnic community-based health system.

- Continued funding of the EHOs/CBHOs, EHO/CBHO registration and recognition, and the recognition and accreditation of EHO/CBHO health workers are critical issues in the health convergence process.

- Key devolved health system issues:

- Amendments to Schedules 2 and 5 of the 2008 Constitution – health and expanded taxation authority to be shared with the states/regions.

- Enactment of related health laws and regulations.

- Sufficient pool of knowledgeable, experienced, and skilled political, administrative, and fiscal health officials at the sub-Union levels.

- Adequate sub-Union revenue sources for the health sector.

- Political will for a devolved health system by the Myanmar government, Tatmadaw, and EAOs.

Leave a Comments